Section 1: An Integrated Vision for Urban Corridors

1.1 The Challenge of Legacy Infrastructure

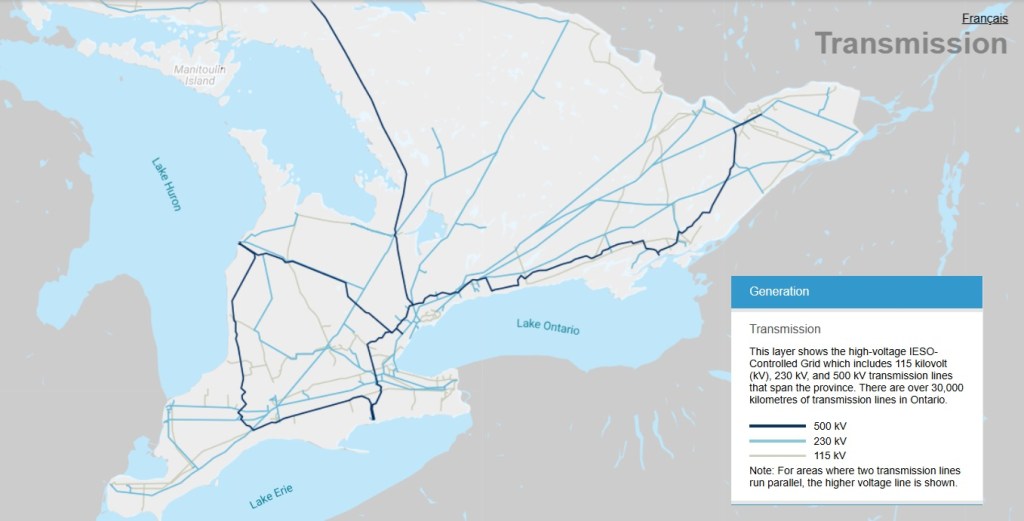

The Greater Toronto Area (GTA), as one of North America’s fastest-growing urban regions, is increasingly constrained by its legacy infrastructure. Among the most prominent and impactful of these are the extensive networks of overhead high-voltage transmission corridors. These corridors, while essential for the region’s electrical grid, represent a significant and multifaceted challenge to sustainable urban development. Spanning vast tracts of land, such as the 1,400 hectares within the City of Toronto alone, these corridors function as profound physical and developmental barriers.1 They fragment communities, inhibit contiguous urban planning, and sterilize thousands of hectares of what would otherwise be prime developable land in a region facing an acute housing and land scarcity crisis.

Beyond the spatial and social costs, this legacy infrastructure model embodies a significant energy inefficiency. High-voltage cables, whether suspended overhead or buried underground, generate substantial quantities of heat as an unavoidable byproduct of electrical resistance and dielectric losses.2 This thermal energy, often referred to as low-grade waste heat, is a direct manifestation of power loss within the transmission system.4 In conventional designs, this heat is simply dissipated into the surrounding soil or atmosphere, representing a continuous and large-scale loss of a potentially valuable energy resource. This paradigm of treating valuable urban land as single-use utility space and thermal energy as a waste product to be discarded is increasingly untenable in the context of 21st-century goals for urban density, energy efficiency, and decarbonization.

1.2 A Synergistic Solution: Land, Power, and Heat

“Our director has read your paper and we would like to publish it in the Policy Engagement section of Engineering Dimensions. He mentioned in particular that it raises interesting technological ideas that could drive public policy.”

This report evaluates an integrated, synergistic solution that reframes these challenges as a singular, self-financing opportunity. The core concept is the creation of a value-generating loop that interconnects three distinct but related initiatives: the modernization of power infrastructure, the strategic development of underutilized urban land, and the creation of a new sustainable energy resource. By burying the overhead high-voltage transmission lines, the project would unlock approximately 8,000 hectares of land for development. The central hypothesis is that the immense market value of this reclaimed land can serve as the primary financing mechanism for both the substantial capital cost of undergrounding the cables and the implementation of a sophisticated waste heat recovery system.

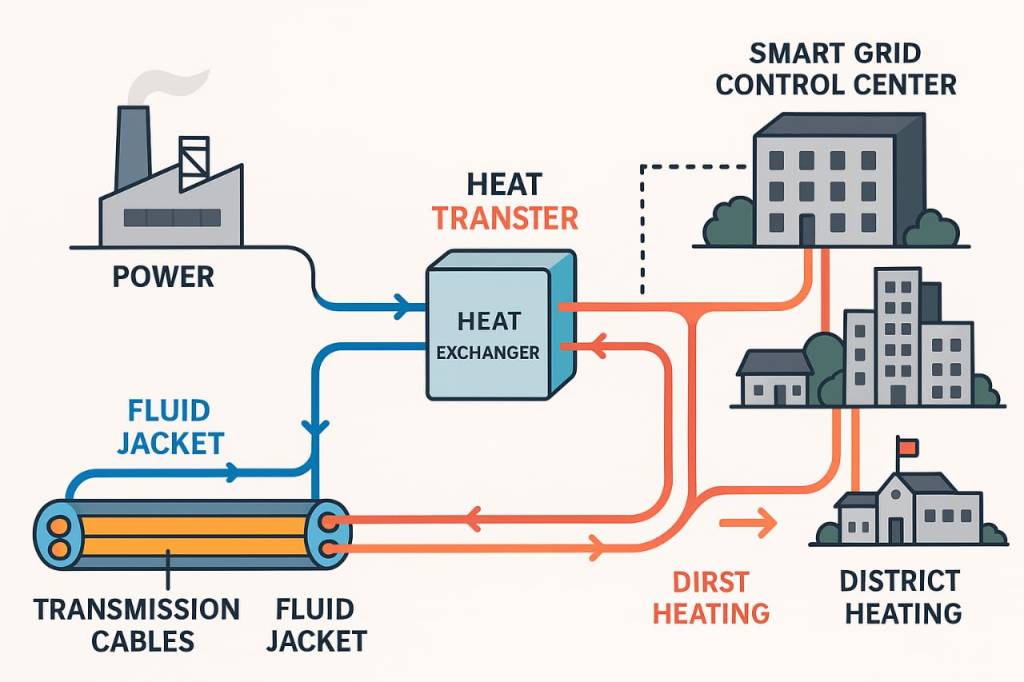

This approach directly addresses a major untapped potential in urban energy systems. Across Europe, it is estimated that waste heat from urban infrastructure could meet approximately 10% of the total building heating demand.5 However, its utilization remains low, not due to technical impossibility, but because of persistent non-technical barriers, including the absence of established business models, unclear regulatory frameworks, and a lack of standardized contracts.6 This proposed initiative provides a unique and powerful catalyst to overcome these obstacles. It intrinsically links the creation of a new, large-scale heat source (the underground cables) with a robust funding stream (the land sales) and a captive customer base (the new developments on that same land), creating the ideal conditions to establish a viable heat recovery utility.

This vision represents a paradigm shift in infrastructure planning, moving from a siloed approach to one rooted in the principles of a circular economy.8 It transforms an underutilized asset (linear land corridors) and a waste stream (dissipated heat) into highly valuable resources: new communities and a source of low-carbon thermal energy for district heating.9 The project would not only modernize the electrical grid but also create a foundational infrastructure for a future regional, low-temperature district energy network. The distributed nature of the undergrounded cables, spanning numerous municipalities, would establish a thermal backbone that could later integrate other opportunistic urban heat sources, such as data centers, wastewater systems, and subway tunnels, which have been successfully demonstrated in case studies like London’s Bunhill project.10 In this way, the initiative acts as a strategic enabler for broader decarbonization and energy resilience goals across the entire GTA.

Furthermore, the project serves to de-risk and future-proof the region’s energy supply. The Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) forecasts significant long-term growth in electricity demand for the GTA.13 Securing new land for transmission corridors is an increasingly difficult and contentious process. By replacing aging overhead infrastructure with new, high-capacity underground cables within existing corridors, this project preemptively addresses future grid capacity requirements. This act of “hardening” the electrical backbone enhances its resilience against climate-related events and ensures that the grid can support the region’s projected economic and population growth, a core priority for system operators.16

Section 2: Unlocking the Asset: Valuation of GTA Transmission Corridor Lands

The financial viability of this integrated initiative is fundamentally dependent on the value of its primary asset: the 8,000 hectares of land reclaimed from the transmission corridors. This section provides a detailed, evidence-based valuation of this land portfolio, grounded in the current dynamics of the GTA real estate market. The analysis recognizes that this is not a simple land sale but a strategic application of Land Value Capture (LVC), whereby the increase in land value created by a public investment (cable undergrounding) is recycled to finance that same investment.

2.1 Delineating the Land Asset

The land in question comprises portions of the extensive Hydro One transmission corridors that traverse the GTA. Within the City of Toronto alone, these corridors extend for 160 km, covering nearly 1,400 hectares.1 The project’s proposed scope of 8,000 hectares (approximately 19,770 acres) represents a massive portfolio that would encompass corridors extending across the regional municipalities of Peel, Halton, York, and Durham. These lands, formerly owned by Hydro One for its transmission system, were transferred to the provincial government and are now managed by Infrastructure Ontario (IO) under the Provincial Secondary Land Use Program (PSLUP).17 This program acknowledges that the primary use of the land is for electricity transmission but establishes a framework for compatible secondary uses, creating a crucial administrative precedent for the proposed development.19

The physical form of the land is defined by the Right-of-Way (RoW) widths required for high-voltage lines. While these are determined on a case-by-case basis, typical RoW widths for Hydro One’s 230kV lines are in the range of 125 to 150 feet (38 to 46 metres), and for 500kV lines, 150 to 200 feet (46 to 61 metres).21 This results in long, linear parcels of land, uniquely suited for creating connected communities, greenways, and integrated infrastructure networks.

2.2 GTA Land Market Analysis (2025)

The valuation of this land portfolio must be situated within the context of the current GTA real estate market. The first half of 2025 has been characterized by a significant market contraction, with total land transaction volume declining 38% year-over-year. This slowdown has affected all sectors, with residential land sales falling by 44% and Industrial, Commercial, and Institutional (ICI) land sales decreasing by 27%.25 This market softness is attributed to developers postponing new projects amidst economic uncertainty and evolving demand forecasts. Despite this challenging environment, the underlying value of well-located, serviceable land in the GTA remains exceptionally high due to long-term growth pressures and supply constraints.

2.2.1 Industrial Land

The industrial land market, while slower than its post-pandemic peak, continues to command premium prices due to persistent scarcity. Recent transactions in 2024 demonstrate a significant variation in value based on location and zoning. Prices per acre range from approximately $1.1 million in Vaughan and Milton to $1.77 million in Burlington, and can reach as high as $4.05 million for a rare, strategically located parcel in Brampton.26 This wide range illustrates that a single blended value for the 8,000-hectare portfolio would be misleading; a granular, location-specific valuation is essential.

2.2.2 Residential Land

The residential land market has adapted to affordability challenges by shifting towards smaller projects on smaller parcels; the median land deal size in 2024 was the smallest in seven years.27 Prices for high-density land, suitable for condominium development, have seen a notable correction. After peaking at nearly $100 per buildable square foot (psf) in late 2024, the average price fell to approximately $52 per buildable psf in the second quarter of 2025, the lowest level since 2017.28 Low-density land for single-family homes, particularly in established suburban municipalities, remains highly valued, with prices having surpassed $1 million per acre several years ago and now reaching multi-million dollar figures in prime locations.29

2.2.3 Commercial, Office, and Retail Land

Investment in the office sector has seen a steep decline, with transaction volumes down 39% year-over-year.25 The value of land zoned for commercial or office use is highly dependent on its potential for conversion to mixed-use or residential development. The retail sector has remained more stable, with investors favoring food-anchored properties and sites with clear redevelopment potential.25

2.3 Revenue Projection Scenarios and Land Value Capture (LVC)

The financial model for this project is predicated on the principle of Land Value Capture (LVC). LVC is a policy approach that enables public authorities to “capture” a portion of the increase in private land value that results directly from public investments, such as new transit or infrastructure, and reinvest those funds to help pay for the initial investment.30 In this case, the act of burying the transmission lines is the direct catalyst that transforms low-value utility corridors into highly valuable, developable real estate. The revenue generated from the sale of this land is therefore a direct capture of this publicly created value uplift. This framework has been used to fund major infrastructure projects globally and has been studied extensively by Canadian bodies like Metrolinx and the Canada Infrastructure Bank.30

Given the scale of the land portfolio, a phased disposition over a multi-decade timeline is necessary to avoid flooding the market and depressing values. The project’s financial structure must therefore be viewed not as a one-time asset sale, but as the active, long-term management of a real estate portfolio. This requires a dedicated governance body with expertise in urban planning, real estate development, and market analysis to manage the phased release of land parcels in coordination with municipal growth plans and economic cycles.

The revenue model must also reflect the diverse character of the corridors. A granular, segment-by-segment valuation is required, mapping the 8,000 hectares and assigning specific land use typologies and corresponding values based on the surrounding municipal context. Corridors passing through the dense urban core of Toronto would be valued for high-density mixed-use development, while those in Peel or Durham might be better suited for industrial or low-density residential uses, each with a vastly different price per acre. Table 1 provides a matrix of estimated land values based on this segmented approach, forming the foundation for a realistic revenue forecast.

Table 1: GTA Transmission Corridor Land Value Matrix (CAD $/Acre), Q2 2025

| Land Use Category | GTA West (Peel, Halton) | GTA Central (Toronto, York) | GTA East (Durham) |

| Industrial | $1,100,000 – $4,100,000 | $2,500,000 – $5,000,000+ | $800,000 – $1,800,000 |

| High-Density Residential | $40 – $60 / buildable sq. ft. | $80 – $135+ / buildable sq. ft. | $35 – $55 / buildable sq. ft. |

| Low-Density Residential | $1,500,000 – $2,500,000 | $2,500,000 – $4,000,000+ | $1,000,000 – $2,000,000 |

| Commercial / Mixed-Use | $1,200,000 – $2,000,000 | $3,000,000 – $6,000,000+ | $900,000 – $1,600,000 |

Note: Values are synthesized estimates based on a review of market reports and specific transactions for Q1/Q2 2025.25 High-density values are presented per buildable square foot, as is standard; conversion to a per-acre value depends on permitted density (FSI/GFA). All values are highly location-dependent and subject to market fluctuations.

Section 3: The Enabling Investment: Technical and Financial Assessment of Cable Undergrounding

The primary capital expenditure of this initiative is the comprehensive program to remove existing overhead high-voltage transmission lines and replace them with a modern underground cable system. This section quantifies this enabling investment, establishing a realistic cost forecast based on technical requirements and relevant precedents from North America and, specifically, Ontario.

3.1 Engineering Scope and Cost Drivers

The project’s scope involves the undergrounding of high-voltage alternating current (HVAC) transmission lines, predominantly the 230kV and 500kV circuits that form the backbone of the Hydro One transmission network supplying the GTA.35 The engineering complexity of such an undertaking is substantial. It extends far beyond simple trenching and includes the construction of specialized transition stations at each end of a buried segment to connect the underground cables to the remaining overhead network, the management of complex urban traffic and logistics, and the careful navigation of a dense web of pre-existing subterranean utilities.37

The cost of undergrounding is significantly higher than constructing new overhead lines, with numerous studies indicating a cost multiplier of 4 to 10 times, and in some cases even more.39 The primary cost drivers are well-established and include:

- Voltage Level: Higher voltages like 500kV require larger conductors, thicker and more advanced insulation, and greater spacing, all of which increase material and installation costs significantly.38

- Urban Density: Construction in dense urban cores is far more expensive than in suburban or rural areas due to traffic control requirements, restricted work hours, the need for more sophisticated excavation techniques (e.g., tunneling vs. open trenching), and the higher cost of labor.

- Geological and Ground Conditions: The nature of the soil and bedrock dictates the excavation methods and costs. Rocky terrain or areas with a high water table can dramatically increase the expense and complexity of trenching and duct bank construction.43

- Circuit Configuration: The cost will vary depending on whether single or double-circuit lines are being installed in a single trench.

3.2 Capital Expenditure Model for Undergrounding

To develop a credible cost model, data from several North American and Ontario-specific sources must be synthesized and adjusted for a 2025 baseline.

A 2010 feasibility study for a 500kV AC undergrounding project in Alberta, a relevant Canadian comparator, produced total project cost estimates ranging from $1.2 billion to $2.1 billion (in 2009 Canadian dollars), depending on the specific scenario and length of the undergrounded segment.44 A U.S. study on 500kV HVDC lines—a reasonable proxy for high-capacity AC systems—found a cost range of $3.9 million to over $8 million USD per mile ($2.4 million to $5 million USD per km).45

More localized data from Ontario, though older, provides a crucial benchmark. A 2005 Ontario Energy Board (OEB) document provided representative unit costs, estimating a 230kV double-circuit underground cable at approximately $6 million CAD per km and a 500kV double-circuit overhead line at $1.8 million to $2.5 million CAD per km.47 Applying a conservative 5x multiplier to the 500kV overhead cost suggests a baseline undergrounding cost of at least

$9 million to $12.5 million CAD per km in 2005 dollars.

To translate these historical figures into a 2025 forecast, it is essential to account for the significant escalation in construction costs over the past two decades. The Statistics Canada Building Construction Price Index (BCPI) for Toronto shows that residential building construction costs, for example, have more than doubled since the mid-2000s.48 Applying a conservative inflation and escalation factor to the 2005 OEB figures results in a 2025 cost estimate that is substantially higher, likely placing 230kV lines in the range of $12-15 million per km and 500kV lines in the range of $20-30 million per km, with significant variation based on urban density. Table 2 presents a structured forecast of these capital costs, segmented by voltage and urban typology, which will serve as the primary cost input for the project’s financial model.

Table 2: Capital Cost Estimates for High-Voltage Undergrounding in the GTA (2025 CAD $/km)

| Voltage / Configuration | Urban Core (e.g., Downtown Toronto) | Dense Suburban (e.g., Mississauga) | Outer Suburban / Industrial |

| 230kV Double-Circuit Line | $20,000,000 – $35,000,000+ | $15,000,000 – $25,000,000 | $10,000,000 – $18,000,000 |

| 500kV Double-Circuit Line | $35,000,000 – $60,000,000+ | $28,000,000 – $45,000,000 | $20,000,000 – $32,000,000 |

Note: These are planning-level estimates derived from a synthesis of North American and Ontario precedents 43, adjusted for inflation to a 2025 baseline using Statistics Canada construction price indices.51 Actual costs are highly project-specific and subject to detailed engineering design.

The project’s implementation must be strategically phased, prioritizing corridors where the projected land value significantly exceeds the estimated undergrounding cost. This approach would allow profits from early, high-value phases (e.g., in the urban core) to cross-subsidize later phases that may have a lower direct return on investment but are crucial for completing the network.

Furthermore, a complete financial assessment must consider the full life-cycle cost. While the upfront capital expenditure for undergrounding is immense, the long-term operational and maintenance (O&M) costs are substantially lower than for overhead lines. Underground systems are protected from severe weather events like ice storms and high winds, which dramatically reduces outage frequency and costly emergency repairs.37 They also eliminate the recurring, significant expense of vegetation management along the corridors.53 These long-term O&M savings represent a tangible, albeit secondary, financial benefit that improves the overall business case for the investment.

Section 4: The Sustainability Dividend: Feasibility of Waste Heat Recovery

The integration of a waste heat recovery system elevates this initiative from a real estate and infrastructure project to a landmark in urban sustainability. This section evaluates the technical and economic feasibility of capturing the thermal energy dissipated by the new underground cables, assessing it not only as a potential revenue stream but also as a critical technical enhancement to the new power infrastructure itself.

4.1 The Thermal Resource

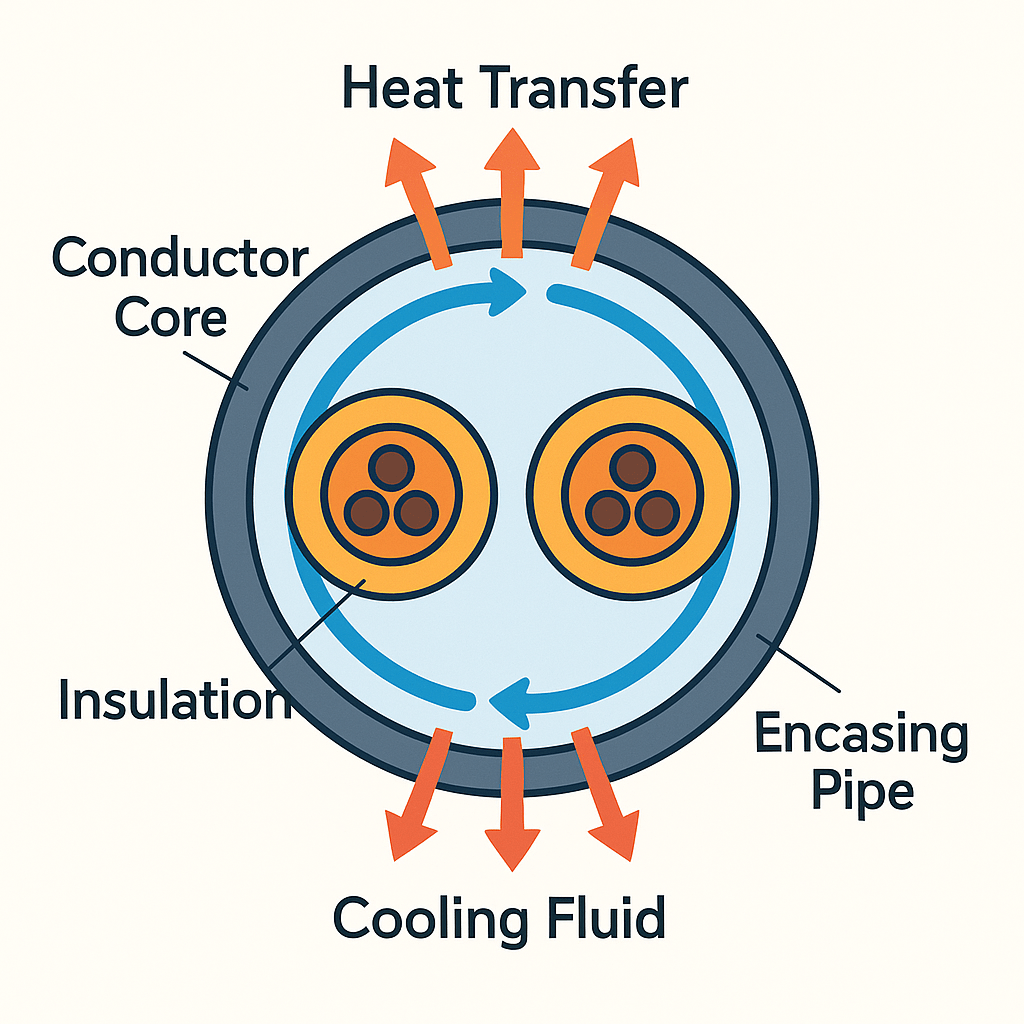

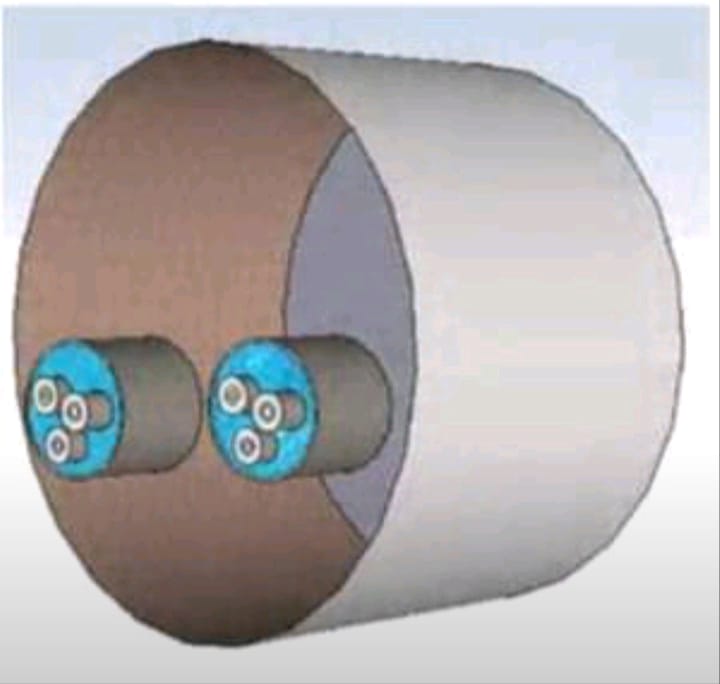

Underground high-voltage cables are a consistent and significant source of low-grade heat. This heat is generated through a combination of resistive losses in the conductor (I2R), dielectric losses in the insulation, and losses from induced currents in the metallic sheath and armour.2 The efficient dissipation of this heat is a primary constraint in cable design; failure to do so can cause the cable’s temperature to exceed its maximum operating limit (typically 90°C for modern cross-linked polyethylene, or XLPE, insulation), which degrades the material, shortens the cable’s lifespan, and reduces its safe current-carrying capacity, or “ampacity”.56

Heat loss is typically quantified in Watts per meter (W/m) and can be calculated using international standards such as IEC 60287.59 For a 132kV cable, total losses can be in the range of 36 to 43 W/m.61 For a 400kV cable, conductor and sheath losses alone can account for approximately 38.6 W/m, with an additional 0.012 W/m from dielectric losses.62 When extrapolated over hundreds of kilometers of new cable, this represents a thermal resource of many megawatts. This heat creates a stable thermal environment in the cable’s vicinity, with tunnel air temperatures potentially reaching 44°C and surrounding soil temperatures exceeding the 50°C threshold where soil begins to dry out, which in turn increases its thermal resistance and traps more heat.63 This creates a reliable, year-round source of low-grade heat that is ideal for recovery.

4.2 Technology Evaluation and Selection

The primary challenge in utilizing this resource is its low temperature, or “grade.” Heat below 100°C has historically been difficult to convert or use cost-effectively.66 A range of technologies exists for this purpose, including Organic Rankine Cycles (ORC) for electricity generation, and various absorption and adsorption systems for heating and cooling.69

However, for the purpose of providing space and water heating to the new developments, the most mature and suitable technology is the water-source heat pump, a category that includes ground-source heat pumps (GSHPs).71 These devices function as “heat upgraders.” They use a refrigeration cycle to absorb the low-grade heat from a source loop (e.g., water circulating through pipes laid alongside the power cables) and transfer it at a higher, more useful temperature (e.g., 55°C to 75°C) to a distribution network, such as a local district heating system.72

The efficiency of a heat pump is measured by its Coefficient of Performance (COP), which is the ratio of heat energy delivered to the electrical energy consumed. A key advantage of using the thermal environment around underground cables as a source is its stability. Unlike air-source heat pumps, whose efficiency plummets in cold weather, a system drawing heat from the ground or a cable tunnel benefits from a relatively constant source temperature year-round, generally between 18°C and 28°C in tunnel environments.71 This results in a consistently high COP, typically in the range of 3.0 to 5.0 for heating applications.74 This means that for every one unit of electricity used to power the heat pump, three to five units of thermal energy are delivered, making it a highly efficient heating method. The COP is directly proportional to the entering water temperature (EWT) from the source; the warmer the heat source, the less work the heat pump has to do, and the higher its efficiency.77

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Low-Grade Heat Recovery Technologies

| Technology | Typical Source Temp. (°C) | Output | Typical Efficiency | Capital Cost ($/kWth) | TRL |

| Ground-Source Heat Pump (GSHP) | 10 – 40 | Heat (50-80°C) | COP: 3.0 – 5.0 | $2,000 – $12,000 | 9 |

| Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) | 80 – 150+ | Electricity | 5% – 9% (net) | CAPEX Intensive | 7-9 |

| Adsorption Heat Battery (e.g., Salt Hydrates) | 60 – 100 | Heat (Storage) | N/A | High / Emerging | 5-7 |

| Reverse ElectroDialysis (RED) | 40 – 80 | Electricity | Low / Experimental | Very High | 4-5 |

Note: TRL = Technology Readiness Level. Capital costs for GSHP are highly variable and include drilling/ground loop installation.79 Data synthesized from.80

4.3 Energy Yield, Economic Value, and Co-Benefits

A pioneering feasibility study conducted in the UK for heat recovery from electrical cable tunnels provides a valuable benchmark. The study’s modeling indicated that up to 460 kW of thermal energy could be delivered to a local heating network from a single recovery point. This translates into an estimated annual saving of 4,000 kWh of combined heat and electrical energy per meter of tunnel.82 Applying these metrics to the extensive network proposed for the GTA suggests a potential energy yield in the hundreds of megawatts, capable of heating tens of thousands of homes.

The economic value of this recovered heat is determined by the cost of the fuel it displaces, which in the Ontario context is overwhelmingly natural gas. Based on current commercial gas rates, this creates a direct and recurring revenue stream.83 This revenue must be weighed against the capital cost of the heat pump systems and the operational cost of the electricity required to run them.85 The high COP of the heat pumps is critical to ensuring a positive operating margin.

However, the most significant value of the heat recovery system may not be the revenue from heat sales, but rather its role in optimizing the primary infrastructure investment. The heat recovery process inherently provides active cooling to the underground cable environment. This cooling is not merely a byproduct; it is a critical engineering benefit. By actively managing the thermal environment and preventing heat buildup, the system ensures the multi-billion-dollar cable assets can operate at their maximum design ampacity without risk of derating due to overheating, particularly during summer peak load conditions.82 This enhances the reliability and capacity of the entire grid and can extend the operational lifespan of the cables, deferring future capital costs. The business case for heat recovery should therefore be framed primarily as a strategic investment in grid optimization and risk mitigation, with the sale of heat providing a valuable secondary revenue stream.

Furthermore, this project can solve a classic “chicken-and-egg” problem for the expansion of district energy (DE) systems. A major barrier to new DE networks is the lack of a reliable, low-cost anchor thermal load to build the system around. The consistent, 24/7 heat output from the transmission corridors provides an ideal baseload thermal resource along the very same linear routes that will be opened for new development. The new residential and commercial buildings constructed on the reclaimed land become the natural, captive customers for a DE system supplied by the heat from the cables running directly beneath them. This creates a powerful synergy, making the project a catalyst for municipal decarbonization efforts that extend far beyond the boundaries of the corridors themselves.

Section 5: The Financial Synthesis: An Integrated Viability Model

This section consolidates the preceding analyses of land value, infrastructure costs, and heat recovery potential into a unified financial model. The objective is to provide a quantitative assessment of the project’s overall economic viability and to test its robustness against key market and operational variables. This model serves as the analytical core of the report, forming the basis for the final strategic recommendations.

5.1 Consolidated Project Cash Flow Analysis

A long-term cash flow model, projected over a 30-year timeframe, is necessary to capture the full cycle of investment and return for a project of this magnitude. The model must be structured to reflect a phased implementation, with costs and revenues staggered over time as different corridor segments are developed sequentially.

- Capital Outflows: The model’s primary costs are the capital expenditures (Capex) for infrastructure. These are dominated by the cost of undergrounding the 230kV and 500kV lines, with inputs drawn from the cost matrix in Table 2. The Capex for the heat recovery system, primarily comprising ground-source heat pumps and associated piping, represents a secondary but significant outflow. Cost estimates for commercial GSHP systems are highly variable, ranging from $2,000 to over 12,000perkWofthermalcapacity(/kWth), heavily influenced by drilling and ground loop installation requirements.79 These costs will be phased in alignment with the undergrounding schedule for each corridor segment.

- Operating Outflows: Annual operating and maintenance (O&M) costs will be incurred for both the underground cable system and the heat recovery network. While O&M for buried cables is lower than for overhead lines, it is not zero. The primary operational cost for the heat recovery system will be the electricity required to power the heat pumps.

- Capital Inflows: The principal source of revenue is the phased sale of the 8,000 hectares of reclaimed land. The timing and value of these inflows will be based on the land valuation matrix in Table 1 and a realistic market absorption schedule, likely spanning 20 to 30 years.

- Operating Inflows: A secondary, recurring revenue stream will be generated from the sale of thermal energy from the heat recovery system to the new developments via a district energy utility model.

The financial profile of this project more closely resembles that of a large-scale real estate development initiative than a traditional utility investment. Unlike utility projects funded through a regulated rate base and recovered over decades from ratepayers, this initiative is financed by substantial, albeit phased, capital inflows from land sales. This necessitates a governance structure with deep expertise in real estate portfolio management, market timing, and urban development, rather than one solely focused on utility engineering.

5.2 Key Financial Metrics and Sensitivity Analysis

The integrated model will be used to calculate the project’s key financial performance indicators, which will determine its self-financing capability.

- Net Present Value (NPV): This will determine if the present value of all future cash inflows exceeds the present value of all cash outflows, indicating overall profitability.

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR): This will calculate the annualized effective rate of return, providing a measure of the investment’s efficiency.

- Payback Period: This will estimate the time required for the cumulative cash inflows to equal the initial investment.

A critical factor influencing these metrics is the time lag between the upfront capital outlay for undergrounding and the subsequent revenue from land sales. This lag, which could be several years for each phase, has a significant negative impact on the time-value-of-money calculations (NPV and IRR). The financial model must meticulously account for this delay. Consequently, strategies to shorten this gap—such as pre-selling development rights to major developers or using innovative financing instruments like green bonds collateralized by future land revenues—will be essential to enhancing the project’s financial attractiveness.

To test the project’s resilience, a sensitivity analysis will be performed on the key assumptions:

- Land Value Fluctuation: +/- 20% variation in projected GTA land values.

- Construction Cost Overruns: +/- 20% variation in undergrounding and heat recovery system costs.

- Discount Rate: Variation in the interest rate used for NPV calculations to reflect different financing costs.

- Land Absorption Rate: Scenarios modeling a faster (20-year) versus slower (40-year) sell-off period.

Table 4: Integrated 30-Year Financial Model Summary (Illustrative Baseline Scenario, CAD Billions)

| Year(s) | Land Sale Revenue | Heat Sales Revenue | Undergrounding Capex | Heat Recovery Capex | O&M Costs | Net Cash Flow | Cumulative Cash Flow |

| 1-5 | $2.5 | $0.05 | ($15.0) | ($2.0) | ($0.1) | ($14.55) | ($14.55) |

| 6-10 | $5.0 | $0.20 | ($15.0) | ($2.0) | ($0.3) | ($12.10) | ($26.65) |

| 11-15 | $8.0 | $0.45 | ($10.0) | ($1.5) | ($0.5) | ($3.55) | ($30.20) |

| 16-20 | $10.0 | $0.70 | ($5.0) | ($1.0) | ($0.7) | $4.00 | ($26.20) |

| 21-25 | $12.0 | $0.90 | ($0.0) | ($0.0) | ($0.9) | $12.00 | ($14.20) |

| 26-30 | $12.5 | $1.00 | ($0.0) | ($0.0) | ($1.0) | $12.50 | ($1.70) |

| Total | $50.0 | $3.30 | ($45.0) | ($6.5) | ($3.5) | ($1.70) | ($1.70) |

Note: This table is illustrative. The actual outcome is highly dependent on the phasing, land value assumptions, and construction costs. This scenario suggests a potential funding gap that would need to be addressed through value engineering, alternative financing, or public subsidy.

5.3 Risk Assessment and Mitigation

A project of this scale and complexity carries significant risks that must be proactively managed.

Table 5: Project Risk and Mitigation Matrix

| Risk Category | Specific Risk | Probability | Impact | Mitigation Strategy | Responsible Party |

| Market | Prolonged downturn in GTA real estate market, reducing land sale revenues. | Medium | High | Phased land disposition over a long-term (30+ year) horizon; establish a land bank to hold assets during downturns; prioritize sales in resilient sub-markets. | Development Corp. |

| Construction | Significant cost overruns and/or schedule delays in complex urban undergrounding work. | High | High | Utilize Public-Private Partnership (P3) models with fixed-price, date-certain contracts; build in substantial contingency budgets (20-30%); conduct extensive geotechnical surveys. | Development Corp. / P3 Partner |

| Technology | Underperformance or high O&M costs of the heat recovery system due to its emerging nature.5 | Medium | Medium | Implement a pilot project on an early phase to validate performance and costs; partner with experienced technology providers with proven track records (e.g., Cellcius 66); secure long-term performance warranties. | Development Corp. / Tech Partner |

| Regulatory | Delays in securing approvals from OEB, municipalities, and environmental agencies; lack of a clear framework for heat sales.6 | High | High | Initiate a parallel policy development stream with the provincial government and OEB; establish a multi-jurisdictional steering committee for coordinated approvals; conduct comprehensive public engagement. | Provincial Govt. / Development Corp. |

Section 6: Framework for Implementation

The successful execution of this transformative project hinges less on its technical components and more on establishing a robust framework for governance, regulation, and stakeholder management. The research consistently shows that the primary barriers to large-scale urban energy projects are non-technical in nature.8 This section outlines a proposed implementation framework designed to navigate these complex challenges.

6.1 Navigating the Regulatory and Stakeholder Landscape

The project’s multi-faceted nature requires engagement with a complex ecosystem of public and private entities. Key stakeholders whose approval and collaboration are essential include:

- Provincial Government: The ultimate authority for enabling legislation, policy direction, and the potential establishment of a new Crown corporation.

- Infrastructure Ontario (IO): The current manager and landowner of the transmission corridor lands on behalf of the Province.19

- Hydro One: The operator of the transmission system, whose technical approval is paramount for any activity within the corridors to ensure the safety, reliability, and maintenance of the grid.16

- Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO): The provincial grid planner, responsible for assessing the project’s impact on and integration with the broader electricity system.13

- Ontario Energy Board (OEB): The economic regulator responsible for approving major transmission projects (“Leave to Construct”) and setting electricity rates. The OEB’s assessment of the project’s cost implications for ratepayers will be a critical hurdle.88

- GTA Municipalities: The various regional and local municipalities whose official plans, zoning bylaws, and development approval processes will govern the new communities built on the reclaimed land.

- Public and Community Groups: Engagement will be crucial to build social license and address concerns ranging from construction disruption and NIMBY (“Not In My Backyard”) opposition to the aesthetic and functional design of the new developments.90

A significant barrier identified in the research is the absence of a clear policy and regulatory framework for urban waste heat recovery in Ontario.6 This “legal vacuum” creates investment risk and uncertainty regarding the sale of thermal energy.7 The project cannot proceed on an ad-hoc basis; it requires the proactive development of new provincial policies. This success of this project is therefore contingent upon the creation of a parallel policy development stream, initiated at the project’s outset. The provincial government, in collaboration with the OEB, must work to establish a new regulatory class for “Urban Thermal Utilities,” create standardized templates for Heat Supply Agreements (HSAs), and clarify the legal status of waste heat as a clean energy resource. This policy work is not a subsequent step but a foundational prerequisite.

6.2 Proposed Governance and Business Model

The project’s unique blend of public infrastructure, real estate development, and energy utility operation is ill-suited to existing institutional structures. Placing it entirely within a traditional utility like Hydro One would misalign with the core real estate and community-building mandate. Conversely, a purely private-sector approach would fail to adequately protect the public interest in this critical infrastructure.

Therefore, the recommended governance model is the establishment of a new, provincially-chartered Crown Development Corporation. This special-purpose entity would be given a clear and focused mandate: to oversee the financing and implementation of the transmission line undergrounding and to manage the subsequent development and disposition of the reclaimed land portfolio. This model offers several advantages:

- Singular Focus: A dedicated corporation can build the specialized, multi-disciplinary expertise in real estate, finance, engineering, and public engagement required for the project.

- Financial Independence: It can operate at arm’s length from general government revenues, with its own balance sheet backed by the land assets, enabling it to raise capital and enter into long-term contracts.

- Coordination Authority: It can act as a single point of contact and coordination among the myriad of stakeholders, streamlining the complex approvals process.

Within this structure, a specific business model for the heat recovery component is required. To overcome the documented barriers of diverging views on the value of heat and long payback periods 8, the Development Corporation would own and operate the heat recovery assets as a subsidiary thermal utility. This utility would sell heat directly to the new homes and businesses in the developments under long-term, stable HSAs.92 This integrated model provides revenue certainty and ensures the sustainability benefits of the project are fully realized.

By structuring the heat recovery component in this manner, the project has the potential to create a new, standardized asset class for institutional investment. While individual urban heat recovery projects are often too small to attract large-scale capital 5, this initiative bundles the thermal infrastructure across 8,000 hectares into a single, utility-grade portfolio. The predictable, long-term cash flows from a large portfolio of HSAs would create an attractive investment vehicle for pension funds and other infrastructure investors seeking stable, inflation-linked returns. This project could therefore serve as a pioneering blueprint, unlocking a significant new stream of private capital for decarbonization infrastructure across Canada.

Section 7: Strategic Recommendations

This report has conducted a comprehensive evaluation of an ambitious proposal to finance the undergrounding of high-voltage transmission lines and the installation of an integrated waste heat recovery system through the subsequent development of 8,000 hectares of reclaimed land in the Greater Toronto Area. The analysis integrates technical feasibility, real estate market valuation, infrastructure costing, and financial modeling to arrive at a set of strategic recommendations.

7.1 Overall Feasibility Assessment

The analysis indicates that the proposed self-financing model is conceptually sound but financially challenging under current market conditions and cost assumptions. The total capital expenditure for undergrounding the extensive network of 230kV and 500kV lines, combined with the heat recovery system, is substantial, likely in the range of $40 to $60 billion CAD or more over a multi-decade period.

While the total potential value of the 8,000 hectares of reclaimed land is also immense, the illustrative financial model (Table 4) suggests that a funding gap may exist. The project’s financial viability is highly sensitive to three key variables:

- The market value of GTA land: A strong, sustained real estate market is essential to generate sufficient revenue.

- The capital cost of undergrounding: The project’s viability improves significantly if costs can be managed towards the lower end of the estimated range through innovation and efficient project delivery.

- The phasing and timing of cash flows: The long lag between upfront investment and subsequent land sale revenue places significant pressure on the project’s net present value.

Conclusion: The project is on the cusp of viability but likely cannot be fully self-financing without supplementary funding mechanisms, significant value engineering to reduce costs, or a strategic partnership with the federal government. However, when considering the significant non-monetized public benefits—including enhanced grid reliability, creation of new housing supply, urban integration, and the establishment of a foundational low-carbon district energy system—a strong case can be made for public investment to bridge any potential funding gap.

7.2 Key Conditions for Success

For this initiative to proceed successfully, several critical conditions must be met:

- Establish a Dedicated Governance Entity: A new, provincially-chartered Crown Development Corporation with a clear mandate and the necessary multi-disciplinary expertise is essential to manage the project’s complexity.

- Adopt a Phased, Portfolio-Based Approach: The project must be implemented sequentially, starting with corridor segments that offer the highest land value-to-cost ratio. The 8,000-hectare land asset must be managed as a long-term portfolio to maximize value and avoid market disruption.

- Proactively Develop a Supportive Policy Framework: The provincial government must work in parallel to create the necessary regulatory and policy framework for urban waste heat recovery, establishing it as a recognized class of clean energy utility.

- Secure Political Championship: The project’s scale, long timeline, and multi-jurisdictional nature require sustained, high-level political support from both provincial and municipal governments to navigate the inevitable challenges.

7.3 Proposed Path Forward

A clear, staged approach is recommended to advance this initiative from concept to reality. The following sequence of actions is proposed:

- Phase 1: Mandate and Seed Funding (Months 1-6):

- Secure a formal mandate and initial seed funding from the provincial government to establish a dedicated Project Task Force, housed within a lead ministry such as Infrastructure or Energy.

- The Task Force’s initial objective will be to develop a detailed project charter and a comprehensive work plan for a full feasibility study.

- Phase 2: Detailed Feasibility and Business Case (Months 7-24):

- Commission a detailed, segment-by-segment GIS-based analysis of the entire transmission corridor network to create a granular and robust land valuation and infrastructure cost model.

- Initiate a formal policy development process with the Ministry of Energy, the OEB, and the IESO to draft the regulatory framework for Urban Thermal Utilities and standardized Heat Supply Agreements.

- Conduct a technical pilot project on a small, representative segment of a corridor to validate heat recovery performance, costs, and operational parameters.

- Develop a comprehensive stakeholder and public engagement strategy.

- Phase 3: Governance and Implementation (Months 25-36):

- Based on the positive outcome of the detailed feasibility study, draft and pass enabling legislation to create the Crown Development Corporation.

- Appoint a board of directors and senior leadership team for the new corporation.

- Initiate the procurement process for the first phase of the project, likely through a Public-Private Partnership (P3) model, to attract private sector expertise and capital.

This initiative represents a generational opportunity to reshape the urban fabric of the Greater Toronto Area, creating more integrated, sustainable, and resilient communities. While the financial and implementation challenges are formidable, the potential rewards—in terms of economic value, housing creation, and long-term energy security—are equally significant, warranting its serious and continued consideration.

Leave a comment