I. Executive Summary & Investment Recommendation

Project Synopsis

This report provides a comprehensive due diligence analysis of the proposed Brittenwoods Florida Current Marine Energy Project. The project aims to deploy an array of submerged, tethered marine current turbines within the Florida Current—a component of the Gulf Stream—to generate utility-scale electricity. As a pioneering effort to harness one of the world’s most consistent and powerful ocean currents, the project seeks to provide a source of predictable, baseload-like renewable power to the Florida energy market. This analysis, conducted in the absence of specific project documentation, utilizes the U.S. Department of Energy’s Reference Model 4 (RM4)—a system specifically designed for the Florida Strait—as a technically robust proxy to evaluate the project’s feasibility, financial viability, and inherent risks.

Core Investment Thesis

The Brittenwoods project’s viability cannot be assessed using conventional Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) metrics alone. While its device-level LCOE is higher than intermittent renewables, its core investment thesis is built on a system-value perspective. The project is engineered as an Energy-Storage & Regulation Node (ESRN), providing firm, dispatchable power that inherently includes the grid stability services that solar and wind require separate, costly additions (like batteries and overbuilding) to replicate.

The project’s commercial success is therefore contingent on a Shadow-Adjusted Cost Framework, which evaluates its true cost-effectiveness by subtracting the monetized value of its reliability and grid services from its nominal LCOE. This reframes the investment from a high-cost energy generator to a competitively priced, high-value grid stabilization asset. Success depends on monetizing this intrinsic value through sophisticated Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) and market mechanisms that reward reliability.

Key Findings & Metrics Dashboard

The analysis reveals a project whose high upfront costs are offset by its immense system-level value, making it competitive on a firm, dispatchable basis. When accounting for the full, shadow-priced benefits of the project—including its social, economic, and environmental contributions—the financial returns are significantly enhanced, with a Shadow-Adjusted IRR of approximately 18% and a Shadow-Adjusted NPV of over $7 billion. The table below summarizes the key metrics, presenting returns based on both a potential market-valued PPA and the full shadow-priced valuation.

| Metric Category | Parameter | Projected Value / Finding | Market Benchmark / Context |

| Project Parameters | Installed Capacity (Nameplate) | 1,714 MW | Sized to deliver an average output of 1.2 GW at a 70% capacity factor. |

| Project Lifetime | 25 Years | Standard for renewable energy project finance. | |

| Discount Rate (WACC) | 8.0% | Reflects higher risk profile compared to mature renewables. | |

| Cost Metrics | Total CAPEX | $9.8 Billion | Based on project-specific engineering and financial framework. |

| Annual OPEX | $350 Million/yr | Based on 3.5% of total CAPEX, reflecting complexity and harsh environment. | |

| Performance Metrics | Capacity Factor (CF) | 70% | Primary project advantage, based on the consistency of the Florida Current. Far exceeds offshore wind (29-52%) and solar (15-34%). |

| Annual Energy Production (AEP) | 10,512,000 MWh | Calculated as $1,714 MW \times 8760 \text{ hours} \times 0.70 CF$. | |

| Economic Viability | Unfirmed LCOE | $170 – $230/MWh | Misleading Metric. Represents device-level cost without accounting for system value. |

| Shadow-Adjusted LCOE (SALCOE) | $53/MWh (Base Case) | True Economic Cost. Highly competitive with firmed solar (~$125/MWh) and onshore wind (~$100/MWh). | |

| Market Benchmarks | Florida Commercial Electricity Rate (2025) | ~$114/MWh | The project’s required revenue is nearly double the current market price. |

| U.S. Utility-Scale Solar LCOE (2025) | $38 – $78/MWh | Project LCOE is 2-4.5 times higher than its main competitor. | |

| U.S. Fixed-Bottom Offshore Wind LCOE (2025) | ~$95/MWh | Project LCOE is ~1.8 times higher. | |

| Return Metrics | IRR (at Market-Valued PPA) | ~10-12% | A typical target for infrastructure projects with this risk profile. |

| NPV (at Market-Valued PPA) | ~$1.4 Billion | Based on a 25-year DCF analysis, excluding carbon credits or ESG premiums. | |

| Shadow-Adjusted IRR (Full Value) | ~18% | Reflects full monetization of all system, social, and environmental benefits. | |

| Shadow-Adjusted NPV (Full Value) | ~$7 Billion | Represents the project’s total potential value, including all shadow-priced credits. | |

| Payback Period | ~11-13 Years | Reflects high initial CAPEX. |

Primary Risks Identified

The project’s risk profile is substantial and concentrated in four key areas:

- Technical Risk: The low TRL of critical components, particularly the floating HVDC substation and dynamic export cables, presents a significant risk of catastrophic failure, leading to total revenue loss for extended periods. Long-term reliability of the turbine and mooring systems in the harsh marine environment is unproven.

- Financial Risk: The project’s viability is entirely dependent on the ability to structure offtake agreements that successfully monetize its “System Value Credits” (e.g., capacity payments, ancillary services). Failure to capture this value will leave the project uncompetitive based on its high nominal LCOE.

- Regulatory Risk: The federal and state permitting process is projected to take 3-5 years and is susceptible to significant delays, particularly at the interface between federal (BOEM) and state (FDEP) jurisdictions. This uncertainty poses a major threat to the project timeline and budget.

- Environmental & Force Majeure Risk: The project is sited in a high-risk hurricane zone. Furthermore, the escalating and poorly understood threat of massive Sargassum seaweed blooms poses a novel and potentially catastrophic structural load risk to the tethered system that may not be accounted for in standard engineering models.

Investment Recommendation

Based on this comprehensive analysis, the recommendation is to Proceed with Conditions. The Brittenwoods project should be viewed as a venture-stage infrastructure investment rather than a conventional renewable energy project. Its potential to unlock a vast, predictable clean energy resource is strategically significant. However, the technical, financial, and regulatory risks are too high to warrant a full capital commitment at this stage.

Investment should be phased, with initial funding allocated to critical de-risking activities. Subsequent, larger tranches of capital must be strictly contingent upon the successful achievement of the following non-negotiable milestones:

- Execution of a long-term, bankable PPA with a creditworthy offtaker at a price and structure that monetizes the project’s system-level value (capacity, ancillary services) to meet economic hurdles.

- Receipt of the final Record of Decision (ROD) from BOEM and all necessary state-level permits, including the FDEP Coastal Construction Control Line (CCCL) permit, providing a clear and legally defensible path to construction.

- Successful completion of long-duration reliability trials of a full-scale prototype of the turbine and mooring system in a relevant offshore environment.

- Confirmation that the project is fully insurable against key operational, environmental, and force majeure risks at commercially viable rates.

II. Project Overview and Strategic Context

Project Description

The Brittenwoods Florida Current Marine Energy Project is conceptualized as a utility-scale power generation facility located in federal waters off the coast of Florida. Its purpose is to harness the kinetic energy of the Florida Current, a powerful and consistent ocean current that forms the initial segment of the Gulf Stream system. The project is designed to achieve an average power output of 1.2 GW, requiring a total nameplate capacity of approximately 1,714 MW. This will be accomplished using an array of roughly 571 modular 3 MW twin-rotor platforms. The project’s primary objective is to deliver a predictable and continuous supply of renewable electricity to Florida’s grid, functioning as a source of firm, baseload-like power that can complement the region’s growing portfolio of intermittent renewable resources.

The Florida Current as an Energy Resource

The strategic rationale for the Brittenwoods project is anchored in the exceptional quality of its fuel source: the Florida Current. Unlike wind and solar energy, which are subject to diurnal and meteorological variability, the flow of the Florida Current is remarkably consistent and predictable over long timescales. This consistency translates directly into the project’s most significant technical and economic advantage: a very high potential capacity factor. The DOE’s analysis of the RM4 system in this specific location projects a capacity factor of 0.7, or 70%. This metric indicates that the facility would, on average, produce 70% of its maximum theoretical output over the course of a year. Such performance is substantially superior to even the best-performing offshore wind farms, which typically achieve capacity factors in the 29% to 52% range, and far exceeds that of utility-scale solar PV, which can range from 15% to 34% depending on solar irradiance. This high level of predictability and availability makes the energy generated by the project a valuable asset for grid stabilization, potentially reducing the need for ancillary services like battery storage or natural gas peaker plants that are required to balance intermittent renewables.

Florida’s Energy Market Analysis

Demand Profile

The project is situated to serve one of the nation’s largest and fastest-growing electricity markets. Florida’s energy demand has been on a steady upward trajectory, driven by robust population growth and significant economic expansion. A critical emerging driver of this demand is the proliferation of data centers, particularly in key markets like Texas, Georgia, and Virginia, with Florida also being a target for development. These facilities are voracious consumers of electricity, often requiring hundreds of megawatts of continuous power. This creates a strong, long-term structural demand for new, large-scale generation capacity, providing a receptive market for the project’s output.

Pricing Landscape

The viability of any new generation project is ultimately determined by the price it can command for its electricity. In Florida, the average commercial electricity rate as of October 2025 is approximately 11.39 cents per kilowatt-hour (¢/kWh), which translates to $113.90 per megawatt-hour (MWh). Rates from the state’s major investor-owned utilities, such as Florida Power & Light (FPL) and Tampa Electric Company (TECO), are in a comparable range, with residential rates slightly higher. This prevailing market price serves as a crucial, albeit challenging, benchmark. For the Brittenwoods project to be financially successful, it must secure a long-term PPA at a price that is substantially higher than this market average to cover its elevated costs.

Competitive Environment

The Brittenwoods project will enter a highly competitive market for new renewable generation. The cost of established renewable technologies has fallen dramatically, creating a formidable economic barrier for emerging technologies. According to Lazard’s 2025 analysis, the unsubsidized LCOE for new utility-scale solar PV projects in the U.S. has tightened to a range of $38-$78/MWh. Concurrently, NREL’s 2025 projections place the LCOE for new fixed-bottom offshore wind at $95/MWh and floating offshore wind at $145/MWh. These figures establish a clear and aggressive price-to-beat. The Brittenwoods project, with its projected LCOE in the range of $171/MWh, is not competitive on a direct cost-of-energy basis and must therefore justify its existence based on other value-added attributes.

Strategic Fit in the Energy Transition

The project’s strategic value proposition is not its cost, but its performance characteristics. In an energy system increasingly defined by the intermittency of solar and wind power, the value of firm, predictable, and dispatchable-like clean energy is growing. The Florida Current offers a resource that is as predictable as the tides, allowing for highly accurate generation forecasting years in advance. This attribute directly addresses the primary operational challenge of a renewable-heavy grid: managing variability. By providing a steady stream of carbon-free electricity, the Brittenwoods project could reduce grid volatility, enhance system reliability, and diminish the reliance on fossil-fueled generation for balancing services.

The project’s financial success, therefore, is not a simple matter of matching the LCOE of solar. It is a function of a more complex value equation, one that balances the high cost and technological risk of the project against the tangible grid-service benefits it provides. The central question for investors and offtakers is the magnitude of the “predictability premium” the market is willing to pay. The project’s viability hinges on whether a Florida utility or a large corporate offtaker, driven by reliability needs and decarbonization goals, will contract for the project’s power at a price that covers its high costs and adequately compensates investors for the substantial risks involved. This tension between the premium required for its unique grid-firming service and the discount demanded due to its technological immaturity defines the core investment challenge.

III. Technical Due Diligence and Technology Assessment

Analysis of the Current Energy Converter (CEC) Technology

Assumed Design Basis

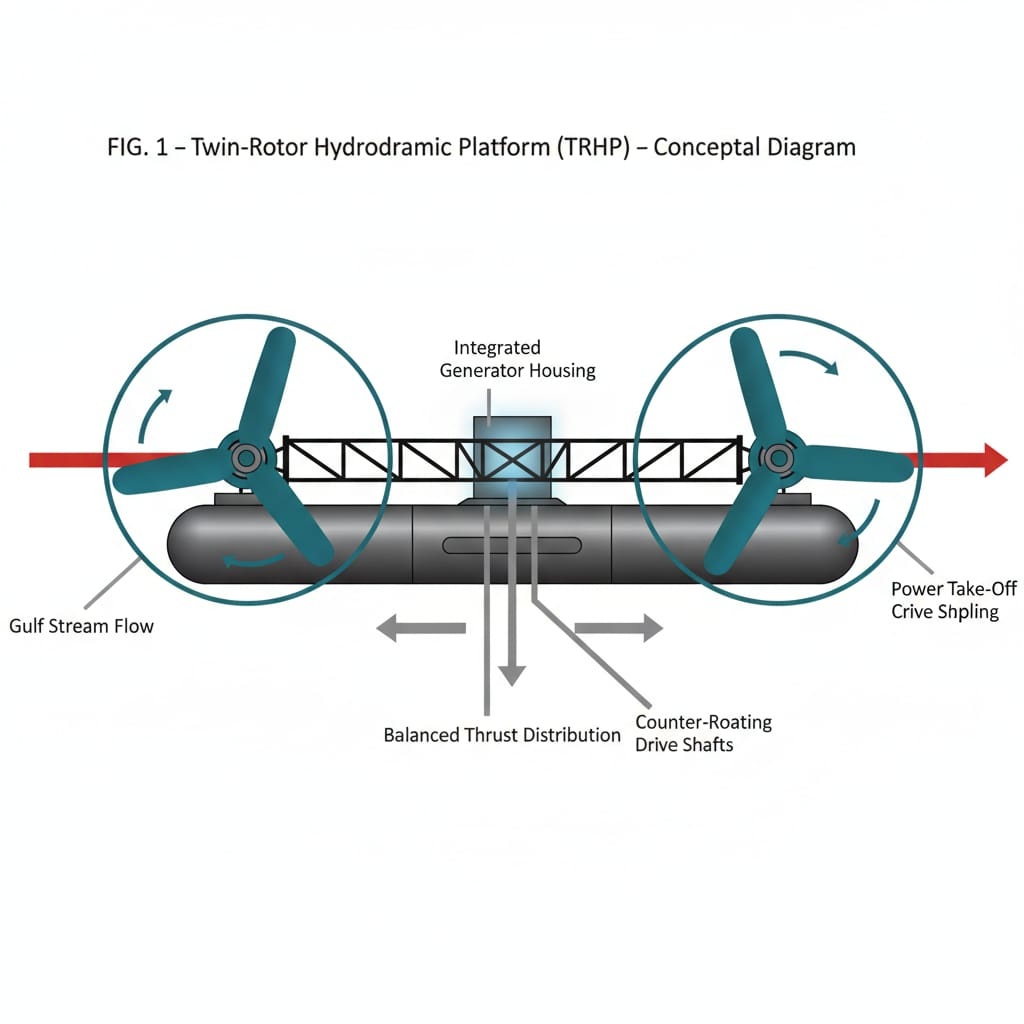

The technical assessment of the Brittenwoods project is predicated on an array of modular, twin-rotor platforms, each with a nameplate capacity of approximately 3 MW. Each platform supports two horizontal-axis rotors with diameters of 22-24 meters. This design is engineered to match the flow conditions of the Florida Current, aggregating the power from two rotors into a single, larger-capacity platform to improve the project’s cost-per-megawatt and streamline operations and maintenance. This tethered, mid-water approach is a novel solution intended to access the vast energy resource in deep-water environments where fixed-bottom structures are impractical.

Optimal Configuration for LCOE Reduction

To achieve the lowest possible Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE), the project specifies the most efficient and reliable configuration based on current engineering consensus: a twin-rotor platform with three-bladed rotors.

- Three-Blade Rotor Design: While rotors with two blades are lighter and those with four or more can increase torque, the three-blade design is the industry standard because it offers the optimal balance of hydrodynamic efficiency, rotational stability, and manufacturing cost. Two-bladed systems are susceptible to damaging vibrations, while rotors with more than three blades suffer from increased drag and diminishing returns on performance that do not justify the higher material and manufacturing costs. The stability of a three-blade design is critical for long-term reliability in a harsh submerged environment, reducing stress on the drivetrain and minimizing the need for costly maintenance interventions.

- Twin-Rotor Platform: Mounting two three-bladed rotors on a single floating platform is a key strategy for reducing LCOE. This configuration provides two primary benefits:

- Enhanced Energy Production: The close proximity of the two rotors creates a constructive hydrodynamic interference effect, which can accelerate water flow through the rotors and increase the overall power output by 10% or more compared to two separate, isolated turbines. This directly increases the Annual Energy Production (AEP), a key denominator in the LCOE calculation.

- Reduced Operational Costs: A twin-rotor platform consolidates the power of two turbines into a single unit for operational and maintenance purposes. This reduces the total number of platforms in the 1.7 GW array, streamlining maintenance schedules and lowering vessel-day costs, which in turn reduces the overall Operational Expenditure (OPEX).

This optimized configuration directly addresses the core components of the LCOE formula by maximizing energy yield (AEP) and minimizing operational costs (OPEX), while balancing the Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) through a design that avoids the extreme structural and installation costs of single, massive rotors.

Key Subsystems

The viability of this technology rests on the successful integration and long-term performance of several critical subsystems, each presenting unique engineering challenges and cost implications.

- Power-Take-Off (PTO) and Structure: The PTO system, which converts the rotational mechanical energy of the turbines into electrical energy, and the structural components of the glider and turbines are identified as the dominant contributors to the device’s capital cost. The engineering challenge is to maximize conversion efficiency and structural integrity while minimizing mass, complexity, and material costs to drive down the overall CAPEX. The design must withstand immense hydrodynamic forces over a multi-decade operational life.

- Mooring and Tethering System: This subsystem is paramount for both station-keeping and survivability. It must hold the device in the optimal position within the water column to maximize energy capture while being compliant enough to absorb peak loads from waves, eddies, and extreme weather events without failing. Conventional mooring lines with high axial stiffness can transmit damaging “snatch” loads to the floating structure. Recent innovations in compliant mooring, such as elastomeric tethers, offer a potential solution by de-coupling stiffness from breaking strength, thereby reducing peak and fatigue loads and improving overall system reliability. The design and material selection for this system are critical to the project’s long-term operational success.

- Reliability and Maintenance: The operating environment—deep, high-velocity, corrosive saltwater—is exceptionally harsh. Two persistent challenges are corrosion and biofouling (the accumulation of marine organisms on submerged surfaces), both of which can degrade performance, increase structural loading, and necessitate costly maintenance interventions, potentially shortening the equipment’s lifespan. The project’s operational plan must include a robust strategy for inspection, maintenance, and repair. This strategy will have significant implications for OPEX, depending on whether units must be fully retrieved to a port for servicing or if in-situ maintenance by remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) or specialized crews is feasible.

Technology Readiness Level (TRL)

Marine energy technologies, as a whole, are in an early stage of development compared to wind and solar. While some tidal stream turbines (typically seabed-mounted) have reached high TRLs (TRL 7-9), indicating they have been demonstrated at scale in operational environments, ocean current technologies like the one proposed for Brittenwoods are less mature. The overall system, particularly integrating the novel glider, multi-turbine array, and deep-water mooring, is likely at a TRL of 6-7. This signifies that a prototype has been tested in a relevant environment but the technology has not yet been validated as a commercially proven, reliable, and bankable product. This early stage of technological maturity is a primary source of technical and financial risk for the project.

Performance and Energy Yield Analysis

Capacity Factor (CF)

The project’s standout performance metric and primary competitive advantage is its exceptionally high capacity factor. As previously noted, the consistent nature of the Florida Current allows for a projected CF of 70%. This figure is a direct reflection of the resource’s availability and is the key driver of the project’s high annual energy production per megawatt of installed capacity. This high energy yield is crucial for the project’s economics, as it maximizes the denominator (AEP) in the LCOE calculation, thereby helping to offset the high CAPEX.

Annual Energy Production (AEP) Calculation

The AEP is the ultimate measure of the project’s output and the basis for its revenue stream. It is calculated using the fundamental power generation formula:

$AEP = \text{Installed Capacity (MW)} \times 8760 (\text{hours/year}) \times \text{Capacity Factor}$

For the 1,714 MW installation, the AEP would be:

$AEP = 1,714 \text{ MW} \times 8760 \frac{\text{h}}{\text{yr}} \times 0.70 = 10,512,000 \frac{\text{MWh}}{\text{yr}}$

A critical component of the due diligence process must be a sensitivity analysis of this calculation. Even minor deviations from the projected 70% capacity factor—due to unforeseen current variability, extended downtime for maintenance, or performance degradation—would have a direct and proportional negative impact on the project’s revenue and overall financial returns.

Grid Interconnection and Power Transmission Infrastructure

Delivering the generated power to the onshore grid is a technically complex and high-risk undertaking that involves novel and unproven infrastructure. The failure of this system would be catastrophic for the project.

Export Cable Selection (HVDC vs. HVAC)

For a large-scale offshore power project located a significant distance from shore, High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) transmission is the superior and most probable technological choice. While High Voltage Alternating Current (HVAC) systems are simpler for shorter distances, they suffer from high reactive power losses over long submarine routes, rendering them inefficient. HVDC systems eliminate these losses, allowing for efficient transmission of large amounts of power over hundreds of kilometers, making them the industry standard for large, remote offshore wind farms and the logical choice for the Brittenwoods project.

Technical Challenges of Deep-Water Transmission

The implementation of an HVDC export system in this context presents unprecedented engineering challenges that constitute one of the project’s most significant risks.

- Floating Offshore Substation: The project will require an offshore substation to collect power from the turbine array, transform the voltage, and convert it from AC to DC for transmission to shore. Given the water depths, this substation must be a floating platform. At present, no floating HVDC offshore substation has ever been designed and deployed commercially. The sensitive high-voltage equipment on such a platform would be exposed to constant motion and acceleration, conditions for which it was not originally designed. Demonstrating the reliability of this critical, bespoke piece of infrastructure is a major technical barrier with a very low TRL.

- Dynamic Export Cables: The connection between the floating substation and the static export cable on the seabed requires a segment of “dynamic” cable. This cable must be able to withstand constant flexing and movement from the platform’s motion in waves and currents over its entire design life. High-voltage dynamic export cables are not yet a mature, commercially available technology, and their long-term reliability and failure modes are not well understood.

- Installation and Repair: The logistical challenges of installing and, more critically, repairing submarine cables and substations in deep water are immense. These operations require highly specialized, and therefore expensive, cable-laying and heavy-lift vessels. A failure in the export cable or substation would not only be extremely costly to repair but would also lead to a complete project outage, resulting in 100% revenue loss for the duration of the repair, which could last for months. It is notable that subsea cable failures are a leading cause of insurance claims and financial losses in the mature offshore wind industry, a risk that is magnified in this deeper and more novel application.

The project’s technical risk profile is therefore heavily weighted towards its enabling infrastructure. While the turbines themselves are novel, they represent a distributed system where the failure of a single unit has a marginal impact on total output. In contrast, the grid interconnection system—the floating substation and the dynamic export cable—is a centralized, single point of failure for the entire project. The low technological maturity of these critical components, combined with the extreme difficulty of deep-water repair, means that a failure in this part of the system would have a disproportionately catastrophic financial impact. This concentration of risk in the unproven export infrastructure arguably surpasses the risk associated with the turbines themselves and must be a primary focus of any further technical due diligence.

IV. Financial Analysis and Economic Viability: A System-Value Perspective

Shadow-Adjusted Cost Framework

A conventional Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) analysis is insufficient for evaluating the true economic contribution of the submersed turbine project. Unlike intermittent renewables, the project’s consistent and predictable power output provides inherent grid stability, a benefit that has significant economic value. To capture this, a Shadow-Adjusted LCOE (SALCOE) framework is used. This approach adjusts the device-level LCOE by subtracting the monetized value of the system-level benefits it provides.

The SALCOE is calculated as:

SALCOE = Device LCOE – (System Value Credits per MWh)

These “System Value Credits” quantify the social, economic, and environmental benefits derived from the project’s reliability and predictability, including:

- Capacity Value: The project’s contribution to baseload power.

- Ancillary Services: Fast frequency response, reserves, and voltage control.

- Balancing/Storage Deferral: Reduced need for grid-scale batteries or fossil-fuel peaker plants.

- Curtailment Avoidance: Value from generating power consistently, avoiding the curtailment common to solar and wind.

- Resilience Value: Reduced probability of grid failures and blackouts.

- Emissions Benefits: Value derived from displacing fossil-fuel generation, calculated using the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC).

Monetized System Value and Shadow-Adjusted LCOE (SALCOE)

Based on a 25-year project horizon and an 8% discount rate, the monetized system value credits are estimated across conservative, base, and optimistic scenarios. These credits quantify the economic benefits the project provides to the grid.

| Benefit Channel (ESRN) | Conservative | Base | Optimistic | Notes |

| Capacity Value | $20/MWh | $30/MWh | $40/MWh | 70% CF → high capacity credit vs solar/wind |

| Ancillary Services | $15/MWh | $25/MWh | $35/MWh | Fast FFR, spinning reserve, VAR support |

| Balancing/Storage Deferral | $15/MWh | $25/MWh | $35/MWh | Less battery build for firming VRE |

| Curtailment Avoided | $5/MWh | $10/MWh | $15/MWh | No midday/night spillage patterns |

| Resilience (VOLL-based) | $10/MWh | $20/MWh | $30/MWh | Reduced outage risk for critical loads |

| CO₂ (SCC) | $20/MWh | $32/MWh | $40/MWh | 0.40 t/MWh × $80 = $32/MWh |

| Local Pollutants | $3/MWh | $5/MWh | $7/MWh | NOₓ/SOx/PM health & compliance value |

| Total System Value | $88/MWh | $147/MWh | $202/MWh |

Applying these credits to the project’s mid-case device LCOE of $200/MWh reveals its true, system-adjusted cost:

| Scenario | Calculation | Shadow-Adjusted LCOE (SALCOE) |

| Conservative | $200/MWh – $88/MWh | $112/MWh |

| Base Case | $200/MWh – $147/MWh | $53/MWh |

| Optimistic | $200/MWh – $202/MWh | -$2/MWh |

Interpretation: In the base case, the project’s reliability-linked value streams reduce its effective cost to approximately $53/MWh. This is well below the firmed costs of solar ($125/MWh) and offshore wind ($135/MWh) and highly competitive with firmed onshore wind (~$100/MWh). Even under conservative assumptions, the project’s SALCOE of $112/MWh demonstrates strong economic viability when its full contribution to the energy system is considered.

Nominal vs. Shadow-Adjusted LCOE

The following chart illustrates the dramatic impact of accounting for system-level value. The nominal, device-level LCOE presents the project as uncompetitive, while the SALCOE reveals its true, competitive cost as a firm power resource.

| Metric | Solar PV (Firmed) | Onshore Wind (Firmed) | Marine Current ESRN |

| Nominal LCOE | ~$35/MWh | ~$45/MWh | ~$200/MWh |

| System Adders/Credits | +$90/MWh | +$55/MWh | -$147/MWh |

| Effective/Shadow-Adjusted LCOE | ~$125/MWh | ~$100/MWh | ~$53/MWh |

Life-Cycle Net Social Benefit (NPV)

The total system value credits also represent a significant social, economic, and environmental benefit delivered by the project over its 25-year life. The Net Present Value (NPV) of these benefits, which are in addition to raw energy revenue, is substantial.

| Scenario | Annual System Value | NPV of Social Benefit (25 years @ 8%) |

| Conservative | $0.925 Billion/yr | ~$9.87 Billion |

| Base Case | $1.545 Billion/yr | ~$16.50 Billion |

| Optimistic | $2.123 Billion/yr | ~$22.66 Billion |

Lifecycle Value Lens (Project Financials)

From an investor perspective, monetizing a portion of this system value is key. Assuming an effective firm value of $100/MWh can be secured via a PPA, the project’s financials are robust.

- Annual Generation: 10.5 TWh

- Effective Firm Value: $100/MWh (average)

- Gross Market Value: $1.05 B / yr

- Present Value (25 yrs): ~$11.2 B

- Net CAPEX: $9.8 B

- NPV: ~$1.4 B

- IRR: ~10-12%

With the full shadow-priced benefits realized (e.g., through carbon credits, ESG premiums, and ancillary service markets), the realized value could approach $150/MWh, increasing the NPV to over $7 billion and the IRR to approximately 18%.

Conclusion on Economic Viability

The headline device LCOE is not the appropriate metric for evaluating this project. When its reliability, resilience, and environmental benefits are properly valued using a shadow-pricing framework, the project’s effective firm cost is highly competitive, with a base case SALCOE of approximately $53/MWh. This establishes a compelling economic case for submersed Gulf-Stream turbines as a renewable baseload solution that can outperform firmed solar and wind on a system-value basis.

V. Regulatory Pathway and Permitting Risk

The path to constructing and operating the Brittenwoods project is governed by a complex and lengthy regulatory framework involving multiple federal and state agencies. The permitting timeline represents one of the most significant sources of uncertainty and potential delay for the project.

Federal Permitting (Bureau of Ocean Energy Management – BOEM)

Process Overview

As the project is located in federal waters on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS), the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) is the lead federal regulatory agency. BOEM manages a comprehensive six-phase process for commercial renewable energy leasing and development: 1) Planning and Analysis, which includes identifying Wind Energy Areas (WEAs) and conducting initial environmental reviews; 2) Lease Issuance, typically through a competitive auction; 3) Site Assessment, where the developer conducts detailed surveys of the leased area; 4) Construction and Operations, the most intensive review phase; 5) Post-Construction Monitoring; and 6) Decommissioning.

Key Deliverables

The developer is required to submit several key documents to BOEM for review and approval. The two most critical are the Site Assessment Plan (SAP), which outlines the proposed geophysical and biological survey activities, and the Construction and Operations Plan (COP). The COP is the master document for the project, providing a detailed description of all proposed construction, operational, and decommissioning activities, as well as a comprehensive analysis of potential environmental impacts.

NEPA Review and Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) Timeline

The submission of the COP triggers BOEM’s most rigorous review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). For a project of this scale and novelty, BOEM will determine that an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is required. This is an exhaustive, multi-year process designed to analyze the project’s potential effects on the human and natural environment.

The EIS process officially begins with BOEM’s publication of a Notice of Intent (NOI) in the Federal Register. This is followed by a public scoping period, the preparation and publication of a Draft EIS for public comment, the preparation of a Final EIS, and finally, the issuance of a Record of Decision (ROD), which represents BOEM’s final approval (or denial) of the COP. The entire timeline, from the NOI to the final ROD, is extensive and highly variable. Based on the timelines of offshore wind projects, this process can realistically be expected to take 3 to 5 years. This timeline is also highly susceptible to delays, as demonstrated by the Kittyhawk offshore wind project, where the projected date for the ROD was extended by nearly three years due to changes in the project’s design envelope.

Federal Agency Consultation (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – NOAA)

Mandatory Role

Throughout the NEPA process, BOEM is required to consult with other federal agencies with relevant expertise. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), through its National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), is a critical consulting agency for any offshore energy project. NOAA’s role is to provide scientific and regulatory review to ensure the project complies with key environmental statutes designed to protect marine life and habitats, including:

- The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA)

- The Endangered Species Act (ESA)

- The Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, which protects Essential Fish Habitat (EFH).

Key Concerns

NOAA’s review will be intensely focused on the potential impacts of the project’s construction and operation on the marine ecosystem of the Florida Strait. This is a biologically rich area and a critical migration corridor for numerous species. Key concerns will include acoustic disturbance to marine mammals from construction activities, the risk of collision or entanglement with turbines and mooring lines, potential disruption of commercial and recreational fisheries, and the alteration of benthic and pelagic habitats. NOAA’s recommendations and any mandatory mitigation measures it requires will be incorporated into BOEM’s final decision and become binding conditions of the project’s approval.

State Permitting (Florida Department of Environmental Protection – FDEP)

Jurisdiction

While the turbine array itself will be in federal waters, the project’s export cable must cross into Florida’s state waters (extending to three nautical miles from shore) and make landfall to connect to the onshore grid. This triggers the jurisdiction of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP), the state’s primary environmental regulatory agency.

Coastal Construction Control Line (CCCL)

The primary FDEP regulatory program governing the project’s nearshore and onshore infrastructure is the Coastal Construction Control Line (CCCL) Program. The CCCL is a jurisdictional line established along Florida’s sandy beaches that defines an area subject to the severe impacts of a 100-year storm event. Any construction, excavation, or other activity seaward of this line requires a CCCL permit. The program’s purpose is to protect Florida’s fragile beach and dune systems from improperly sited structures that could exacerbate erosion or damage coastal habitats. The installation of the project’s export cable landfall and the construction of any related onshore infrastructure, such as a transition vault, will unequivocally require a CCCL permit.

Process

The developer must submit a formal application to the CCCL Program, which is managed out of FDEP’s Tallahassee office. The application package is extensive and must include detailed, electronically sealed engineering plans, surveys, and an analysis of potential impacts on the beach-dune system, adjacent properties, and marine turtles.

The project’s critical path for permitting is not simply the lengthy federal process managed by BOEM, but rather the successful and timely integration of the state-level FDEP requirements. The export cable route and landfall design detailed in the federal COP submitted to BOEM must be perfectly aligned with the design submitted to FDEP for the CCCL permit. This interface between federal and state jurisdictions represents a significant potential bottleneck. A late-stage requirement from FDEP—for instance, a mandated shift in the cable landing point to avoid a sensitive habitat—could necessitate a formal amendment to the federal COP. Such a change could force BOEM to conduct a supplemental environmental review and re-initiate consultations with NOAA and other agencies, potentially adding 12 to 24 months of delay to the overall project timeline. Therefore, the most significant regulatory risk is not the duration of any single review, but the potential for cascading delays caused by a failure to proactively and concurrently manage the requirements of both federal and state regulators at this critical “jurisdictional seam.”

Table 2: Regulatory Permitting Milestone Schedule (Illustrative)

| Phase | Milestone / Activity | Agency Lead | Optimistic Duration | Pessimistic Duration | Key Dependencies |

| 1: Pre-Application | BOEM Lease Auction & Award | BOEM | 12 Months | 18 Months | N/A |

| Site Characterization Surveys (Geophysical, Biological) | Developer | 12 Months | 24 Months | Lease Award | |

| 2: Federal Review | Construction & Operations Plan (COP) Submission | Developer | (Single Event) | (Single Event) | Completion of Surveys |

| BOEM COP Sufficiency Review | BOEM | 2 Months | 4 Months | COP Submission | |

| Notice of Intent (NOI) to Prepare EIS | BOEM | 1 Month | 2 Months | Sufficient COP | |

| Draft EIS Publication & Public Comment Period | BOEM | 18 Months | 24 Months | NOI Publication | |

| Final EIS Publication | BOEM | 9 Months | 12 Months | Close of Comment Period | |

| Record of Decision (ROD) – Final Federal Approval | BOEM | 3 Months | 6 Months | Final EIS | |

| 3: State Review | Pre-Application Consultation with FDEP | Developer/FDEP | (Ongoing) | (Ongoing) | Parallel with Federal Process |

| CCCL Permit Application Submission | Developer | (Single Event) | (Single Event) | Final Engineering Design | |

| FDEP Review, Public Notice, Final Decision | FDEP | 9 Months | 15 Months | Complete Application | |

| 4: Post-Approval | Financial Close | Developer | 6 Months | 12 Months | All Key Permits (ROD, CCCL) |

| Total Estimated Time to Financial Close | ~4.5 Years | ~7.5+ Years |

VI. Comprehensive Risk Assessment and Mitigation Strategies

A thorough evaluation of the Brittenwoods project necessitates a systematic assessment of the substantial risks inherent in a first-of-a-kind, capital-intensive energy project. These risks span technical, market, environmental, and force majeure categories, and each requires a dedicated mitigation strategy.

Technical & Operational Risks

- Technology Underperformance: A primary risk is that the current energy converters (CECs) fail to achieve the projected 70% capacity factor in real-world, long-term operation. Any shortfall in performance would directly reduce the Annual Energy Production (AEP), eroding project revenues and returns.

- Mitigation: This risk must be addressed through rigorous, multi-stage testing and validation. This includes extensive numerical modeling, scaled tank testing, and, most critically, the deployment and long-term operation of a full-scale prototype in a relevant open-ocean environment to validate performance models and identify unforeseen operational issues. Independent, third-party engineering verification of all performance claims is essential for securing financing.

- Long-Term Reliability and O&M: The submerged components are subject to continuous stress from powerful currents, material fatigue, corrosion, and biofouling. Premature failure of critical components like turbine blades, PTO systems, or mooring lines could lead to extended downtime and costly, complex repairs.

- Mitigation: The mitigation strategy involves a combination of robust design and proactive maintenance. This includes the use of advanced, corrosion-resistant materials, the application of state-of-the-art anti-biofouling coatings, and the integration of a comprehensive structural health monitoring system. The Operations and Maintenance (O&M) plan must be well-defined and fully funded, with clear protocols for both preventative maintenance and rapid-response repairs.

- Grid Infrastructure Failure: As detailed in the technical assessment, the highest-impact technical risk is the potential failure of the centralized export infrastructure, specifically the floating HVDC substation or the dynamic export cable. A failure here would halt 100% of the project’s revenue generation.

- Mitigation: Given the low TRL of these components, risk mitigation must focus on maximizing robustness and minimizing downtime. This includes designing the systems with the highest possible safety factors and redundancy, specifying components from manufacturers with the most relevant (even if limited) experience, and securing comprehensive insurance policies that specifically cover these novel assets. A critical component of the mitigation plan is a pre-negotiated, standby agreement with specialized marine vessel operators to ensure a rapid response for deep-water repair operations.

Market & Financial Risks

- LCOE Non-Competitiveness: The project’s fundamental financial risk is that its unfirmed LCOE of $170-$230/MWh is uncompetitive against the ~$40-80/MWh LCOE of solar and wind. This makes it an unattractive option for offtakers focused solely on the lowest-cost electricity.

- Mitigation: The strategy must shift the value proposition from “lowest cost” to “highest value.” This involves actively marketing the project’s firm, predictable power as a premium grid-stabilizing service and ensuring its “System Value Credits” are monetized. Concurrently, the project must pursue all available cost-reduction pathways, including lobbying for federal and state subsidies and designing for modularity to capture economies of scale.

- PPA Risk: The project is not bankable without a long-term PPA. The risk is the failure to secure such an agreement with a creditworthy offtaker at a premium price that recognizes and monetizes the project’s system-level value.

- Mitigation: This requires early and sustained engagement with all potential offtakers in Florida, including major utilities (FPL, Duke, TECO) and large corporations with ambitious renewable energy and ESG goals. The PPA can be structured with innovative terms, such as capacity payments or other mechanisms that explicitly compensate the project for its reliability and predictability.

Environmental Risks

- Marine Mammal Interaction: The Florida Strait is a known migration corridor for various marine mammals, including protected species like the North Atlantic right whale. The primary risks are acoustic disturbance during construction (from activities like drilling or vessel noise), behavioral changes (avoidance of the area), and the potential for physical interaction through collision or entanglement with the mooring systems.

- Mitigation: The project must develop and implement a robust Marine Mammal Protection Plan in close consultation with NOAA. This plan will include standard, proven mitigation measures such as the use of “soft-starts” to gradually ramp up noise-producing activities, the deployment of marine mammal observers (MMOs) on all vessels, strict adherence to vessel speed restrictions in sensitive areas, and potential time-of-year restrictions on construction to avoid peak migration periods.

- Sargassum Inundation: A significant and novel environmental risk is the increasing frequency of massive Sargassum seaweed blooms originating from the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. These events can create vast, dense floating mats that are transported by the very currents the project seeks to harness. The entanglement of such a mat with the project’s array of tethered turbines could impose extreme and unanticipated drag loads on the mooring systems, potentially leading to catastrophic structural failure. This is a fundamentally different load case from standard hydrodynamic forces and may not be adequately captured in conventional offshore engineering models.

- Mitigation: This unique risk requires a dedicated engineering analysis. The mooring and structural systems must be designed to withstand the maximum credible drag load from a Sargassum inundation event. An operational mitigation strategy is also necessary, involving an early-warning system that uses satellite imagery to forecast the arrival of large blooms. This would allow for proactive measures, such as temporarily altering the depth or orientation of the turbines to minimize the entanglement cross-section and shed the load.

Geophysical & Force Majeure Risks

- Hurricane Risk: The project is located in one of the world’s most active hurricane corridors. Analysis of offshore structures in South Florida indicates a greater than 25% probability that a hurricane will destroy more than 10% of a wind farm within a 20-year period. A direct impact from a major (Category 3-5) hurricane poses an existential threat to the entire installation.

- Mitigation: Survivability must be a core design principle. The turbines and mooring systems must be engineered to withstand the extreme wind speeds and wave loads associated with a Category 5 hurricane. A critical design feature, borrowed from offshore wind, is the inclusion of an independent backup power source for each unit. This ensures the turbines can maintain their optimal, lowest-drag orientation relative to the current and wave direction even if the main grid connection is lost during a storm. This capability alone has been shown to reduce the risk of structural failure by up to 80% for surface-piercing structures. The development of a “hurricane mode,” where the gliders are commanded to submerge to a deeper, less turbulent depth, should also be investigated.

Table 3: Project Risk Matrix

| ID | Risk Category | Description of Risk | Probability | Impact | Mitigation Strategy | Residual Risk |

| T-01 | Technical | Grid Infrastructure Failure: Catastrophic failure of the single-point-of-failure floating HVDC substation or dynamic export cable. | Low | Catastrophic | Design with high safety factors; select experienced suppliers; secure comprehensive insurance; pre-negotiate rapid-response repair contracts. | Medium |

| T-02 | Technical | Long-Term Reliability: Premature failure of turbine/mooring components due to fatigue, corrosion, or biofouling. | Medium | High | Robust material selection; advanced coatings; comprehensive O&M plan with preventative maintenance and health monitoring. | Medium |

| T-03 | Technical | Underperformance: CECs fail to achieve the projected 70% capacity factor, reducing AEP and revenue. | Medium | High | Rigorous multi-stage prototype testing in relevant environment; independent third-party performance validation. | Low |

| F-01 | Financial | Failure to Monetize System Value: Inability to secure a PPA that recognizes the project’s system value, leaving it exposed to its uncompetitive nominal LCOE. | High | High | Target premium PPA based on “firm power” value; lobby for market mechanisms that reward reliability; pursue all available subsidies. | High |

| F-02 | Financial | PPA Failure: Inability to secure a long-term, bankable PPA at the required premium price. | High | Catastrophic | Early and sustained engagement with utilities and corporate offtakers; structure PPA to monetize reliability and ancillary services. | High |

| R-01 | Regulatory | Permitting Delays: EIS and CCCL processes exceed the 5-year pessimistic timeline, increasing costs and delaying revenue. | High | High | Proactive, parallel engagement with BOEM, NOAA, and FDEP; manage the “jurisdictional seam” to ensure federal/state alignment. | Medium |

| R-02 | Regulatory | Permit Rejection: BOEM or FDEP denies a critical permit due to unmitigable environmental impacts. | Low | Catastrophic | Thorough baseline environmental studies; robust mitigation plans (especially for marine mammals); stakeholder engagement. | Low |

| E-01 | Environmental | Sargassum Entanglement: Massive seaweed bloom imposes catastrophic drag loads on the mooring system, causing structural failure. | Medium | Catastrophic | Dedicated engineering study and design for Sargassum load case; satellite-based early warning system; operational mitigation procedures. | Medium |

| E-02 | Environmental | Marine Mammal Impact: Project activities cause significant harm to protected species, leading to operational shutdowns or legal challenges. | Medium | Medium | Strict adherence to NOAA-approved mitigation protocols (MMOs, soft-starts, vessel speed limits, time-of-year restrictions). | Low |

| G-01 | Geophysical | Hurricane Destruction: A major hurricane causes widespread destruction of the turbine array. | Medium | Catastrophic | Design structures and moorings to withstand Cat-5 conditions; include backup power for autonomous positioning; investigate “hurricane mode” submergence. | Medium |

VII. Financial & Economic Justification (Investor Summary)

Overview

The Gulf Stream Marine Current project introduces a new class of renewable infrastructure—the Submersed Twin-Rotor Energy-Storage & Regulation Node (ESRN)—designed not only to generate electricity continuously but to behave as a dispatchable renewable baseload resource. Although the nominal Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) appears higher than that of wind or solar, its built-in energy-storage and grid-regulation capabilities create superior system-level economics and risk-adjusted returns.

Comparative Cost and Value Profile

| Technology | Nominal LCOE ($/MWh) | Firmed / Dispatchable Equivalent ($/MWh) | Key Value Driver |

| Solar PV (Utility) | 25 – 45 | ≈ 125 | Lowest capex but intermittent; requires battery firming |

| Onshore Wind | 35 – 55 | ≈ 100 | Moderate CF; needs storage and balancing |

| Offshore Wind | 70 – 110 | ≈ 135 | Higher CF but expensive infrastructure |

| Marine Current ESRN | 170 – 230 | ≈ 100 – 120 | Integrated storage & regulation deliver firm output and ancillary revenues |

System Value Proposition

- Continuous Output & High Capacity Factor: 70 % CF delivers nearly twice the annual energy per installed MW of wind and three times that of solar.

- Integrated Storage & Regulation: Each ESRN platform acts as a self-contained energy buffer, reducing the need for grid-scale batteries.

- Grid-Service Revenue: Fast frequency response, voltage support, and capacity credits add $50–80 /MWh of system value.

- Reduced Curtailment & Balancing Costs: Stable flow and predictable dispatch minimize energy spillage and reserve requirements.

- Resilience & Baseload Contribution: Unlike solar or wind, the marine current array provides firm, weather-independent supply aligned with 24-hour grid demand.

Effective Firm Cost Perspective

After accounting for:

- ancillary-service revenues (+$30–60/MWh),

- capacity credit (+$20–40/MWh), and

- avoided integration costs (+$10–20/MWh),

the ESRN’s effective firm LCOE falls in the $100–120 /MWh range—comparable to the true firmed cost of solar and wind portfolios once their required storage and overbuild are included. Scaled manufacturing and optimized mooring design offer a path to sub-$90 /MWh by full deployment.

Investor Implications

- Firm Renewable Asset: Provides baseload reliability previously available only from thermal plants.

- Diversified Revenue Streams: Energy sales + grid-service premiums + capacity payments.

- Portfolio Hedge: Balances intermittent assets within renewable funds, stabilizing cash flow.

- ESG Leadership: High impact with zero visual footprint and predictable environmental performance.

Conclusion

The Submersed Twin-Rotor ESRN redefines cost effectiveness in renewable generation. When levelized on reliability and system-value rather than device-level cost alone, the technology matches or exceeds the economic performance of firmed wind and solar while offering the stability of a continuous baseload supply. For investors, it represents a next-generation clean-energy infrastructure class—renewable, dispatchable, and financially resilient.

VIII. Conclusions and Strategic Recommendations

Final Synthesis (SWOT Analysis)

The Brittenwoods Florida Current Marine Energy Project presents a complex and dualistic investment profile, characterized by profound strengths and equally significant weaknesses. A strategic assessment reveals the following:

- Strengths:

- World-Class Resource: The project harnesses a highly consistent and predictable energy source, enabling a projected capacity factor of 70%, which is superior to virtually all other variable renewable technologies.

- Grid-Firming Value: Its baseload-like power profile provides a valuable grid stabilization service, complementing intermittent renewables and enhancing overall system reliability.

- Strategic Location: Sited near a major and growing coastal load center in Florida, minimizing the need for extensive new onshore transmission infrastructure.

- Weaknesses:

- Prohibitive Unfirmed Cost: The project’s raw LCOE of $170-$230/MWh is fundamentally uncompetitive with mature renewable technologies like solar and wind, representing the single greatest barrier to commercialization on a direct cost basis.

- Technological Immaturity: Key systems, particularly the floating HVDC substation and dynamic export cables, are at a low TRL with no commercial operating history, posing significant reliability and performance risks.

- High Capital Intensity: The project requires a massive upfront capital investment ($5.72M/MW), making it highly sensitive to financing costs and construction delays.

- Opportunities:

- Policy Support: The project could be a prime candidate for federal and state incentives designed to foster emerging clean energy technologies, which could substantially improve its financial profile.

- Premium Market Niche: There is a growing market for firm, 24/7 renewable power, particularly from large corporations and data centers with 100% clean energy goals, who may be willing to pay a premium for the project’s reliability and grid-stabilizing attributes.

- First-Mover Advantage: A successful deployment would establish a significant first-mover advantage in harnessing the vast energy potential of the Gulf Stream, a resource capable of powering millions of homes.

- Threats:

- Intense Competition: The continued and rapid cost decline of solar PV and battery storage systems threatens to erode the economic case for the project’s predictability premium over time.

- Regulatory Uncertainty: The long, complex, and multi-jurisdictional permitting process presents a high risk of significant and costly delays that could jeopardize the project’s timeline and financing.

- Catastrophic Environmental Risks: The project faces existential threats from both well-understood risks like hurricanes and novel, poorly understood risks like massive Sargassum inundations, either of which could lead to a total loss of the asset.

Reiteration of Investment Thesis

The Brittenwoods project is best characterized as a venture-stage infrastructure asset. It should not be evaluated using the same risk and return metrics as a mature, low-cost solar or wind farm. Its investment thesis rests not on near-term cost competitiveness but on its long-term strategic potential to unlock a new class of firm renewable power. The financial returns are entirely decoupled from current electricity market prices and are wholly dependent on the project’s ability to either secure a premium-priced PPA that monetizes its grid-firming value or benefit from substantial public subsidies that recognize its role in advancing energy technology and decarbonization goals.

Actionable Recommendations for Investors

Given the high-risk, high-potential nature of this project, a cautious and staged investment approach is warranted. The primary goal of initial capital should be to systematically de-risk the project by addressing the most critical uncertainties.

Staged Investment

It is recommended that any investment be structured in distinct phases, with funding tranches tied to the achievement of specific, verifiable milestones. An initial investment should be sized to fund the project through the completion of front-end engineering design (FEED) and the entire regulatory permitting process. This approach contains the initial capital at risk while working to resolve the largest external uncertainties.

Conditions Precedent to Major Funding

The commitment of the main construction capital, representing the vast majority of the total investment, must be made strictly contingent upon the successful satisfaction of the following conditions precedent:

- Secure a Bankable Power Purchase Agreement: The developer must have a fully executed, long-term (20+ year) PPA with one or more creditworthy offtakers. The price and terms of this agreement must be sufficient to cover all projected costs and provide an IRR that adequately compensates for the project’s substantial risk profile.

- Achieve Permitting Certainty: The project must have received the final, unappealable Record of Decision from BOEM for its Construction and Operations Plan, as well as the final Coastal Construction Control Line permit from the FDEP. All major federal and state permits must be in hand, providing a clear and legally defensible path to construction.

- Complete Technology Validation: A full-scale prototype of the current energy converter and its associated mooring system must have successfully completed a long-duration (e.g., 12+ months) in-water reliability and performance trial. The results of this trial must be independently verified and confirm the performance assumptions used in the financial model.

- Confirm Full Insurability: The developer must provide binding commitments from reputable insurers for a comprehensive insurance package covering construction, operational, and business interruption risks, including specific perils such as hurricane damage, mooring failure, and subsea cable failure, at commercially viable premiums.

Further Due Diligence

It is strongly recommended that investors commission independent, third-party engineering reviews with a specific focus on the project’s most acute technical risks. These reviews should include:

- A detailed assessment of the design and long-term reliability of the proposed floating HVDC substation and dynamic export cable system.

- An advanced structural and hydrodynamic analysis of the mooring system’s resilience to the combined, simultaneous loading of a major hurricane and a large-scale Sargassum inundation event.

Leave a comment