The evolution of Jamaica’s macroeconomic landscape has been defined by an aggressive accumulation of foreign exchange (FX) reserves, which reached approximately US$6.1 billion by late 2025. While official narratives frame these buffers as a “fortress balance sheet” for stability, a re-evaluation of long-term data since 2010 reveals an amorphous economic framework. In this system, the Bank of Jamaica (BOJ) frequently intervenes to counteract the natural appreciating effects of Direct Remittance Inflows (DRI), effectively “sterilizing” wealth into liquid reserves rather than allowing it to be reinvested into productivity-enhancing sectors. Furthermore, a persistent “inefficiency factor” in economic policy explains why even record-breaking debt reduction has failed to translate into significant GDP growth, with post-COVID performance reflecting a recovery to a pre-crisis production base rather than a new era of structural expansion.

Comparative Analysis of Foreign Exchange Reserves Per Capita

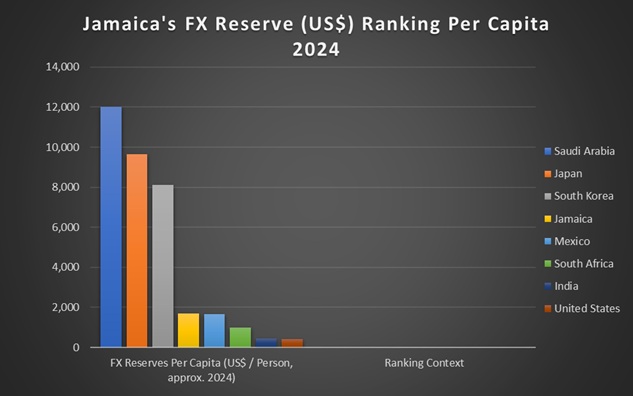

On a per-capita basis, Jamaica’s reserve holdings of approximately US$1,696 exceed several major world economies, placing it within the lower-middle range of the G20 nations.

| Nation | FX Reserves Per Capita (US$ / Person, approx. 2024) | Ranking Context |

| Saudi Arabia | 12,022 | G20 Top Tier |

| Japan | 9,654 | G20 Top Tier |

| South Korea | 8,124 | G20 Top Tier |

| Jamaica | 1,696 | Lower-Middle G20 Equivalent |

| Mexico | 1,667 | G20 Lower Range |

| South Africa | 993 | G20 Lower Range |

| India | 434 | G20 Lower Range |

| United States | 419 | G20 Lower Range |

This high-reserve posture stands in stark contrast to the fastest-growing economies in Africa, such as Ethiopia and Rwanda, which maintain significantly lower buffers—as low as US$31 per capita—while achieving GDP growth rates above 5 percent. This suggests that Jamaica’s “excess” reserves may represent “dead capital”—liquid assets locked in low-yielding foreign securities that fail to drive domestic productivity.

The DRI-Reserve Trap: Counteracting Appreciation at the Expense of Growth

An analysis of the relationship between Jamaica’s stock price index and the exchange rate reveals a unique investment framework. Private capital for economic development is often held exclusively within the overlapping boundaries of investment returns between the Jamaica Stock Exchange (JSE) and the FX markets.

Counteracting DRI Appreciation

The macroeconomic consequences of Direct Remittance Inflows (DRI) create natural appreciating pressure on the JMD. However, the BOJ often intervenes by selling US dollars outside of normal market values to manage these effects in an effort to make “liquidity adjustments”.

- Forced Depreciation: Market interventions that force liquidity at new, depreciated levels of the JMD serve to counteract DRI appreciation. This allows dealers to resell accumulated foreign currency back to the central bank at rates that ensure continued JMD liquidity and further devaluation.

- Resource Misallocation: This “counter-appreciation” impact results in foreign exchange being hoarded in the Net International Reserves (NIR) rather than being reinvested to boost productivity.

- Speculative Cycles: This framework incentivizes a cycle where investors rush to optimize equity returns when the JMD is stable, and shift to FX gains when it is devalued. This likely explains why Jamaica reported one of the highest Stock Exchange Indices in the world between 2011 and 2015, despite anemic growth in the real sector.

The Paradox of Jamaican “Import Substitution”: Repackaging vs. Value-Added

The traditional defense for high reserves is the need to cover a massive import bill. However, this re-evaluation suggests that Jamaica’s trade deficit persists because the government-incentivized sectors focus on a shallow definition of import substitution.

The Failure of the Current Model

Proponents of structural reform argue that manufactured and semi-manufactured goods are often imported and merely repackaged, which does not constitute the value-added production necessary to grow the economy.

- The Monopoly Problem: As noted by Lisa Hanna, the current import substitution model gives producers a guaranteed local market with the expectation of future efficiency, but in reality, this only creates monopolies. These monopolies are incentivized to exploit the local market through higher prices while ignoring the export market.

- Devaluation Ineffectiveness: The Jamaica Manufacturers and Exporters Association (JMEA) has highlighted that the country is not benefiting from currency devaluation because it lacks a robust export base outside of tourism. Growing value-added exports is identified as a “must-fix” issue.

- Inefficiency and Protectionism: In sectors like poultry, the “broken policy model” shields local producers from global competition through high tariffs (up to 260%) while their production remains heavily dependent on imported feed and soy. This “shields inefficiency” rather than fostering innovation.

The Inefficiency Factor: Why Debt Reduction Has Not Triggered Growth

A fundamental paradox of the Jamaican economy is the disconnect between fiscal discipline and economic expansion. Over the past decade, Jamaica has successfully reduced its public debt-to-GDP ratio from nearly 150 percent in 2013 to 62.4 percent by March 2025. Despite this “enviable track record,” real growth has remained anemic, averaging only 0.1 percent to 0.7 percent over the last decade.

Highly Inefficient Investment

This “growth puzzle” is largely explained by a persistent inefficiency factor in Jamaican investment and policy.

- Allocative and Technical Inefficiency: This factor captures both allocative inefficiencies (failing to react optimally to input prices) and technical inefficiencies (employing excessive inputs for minimal outputs).

- High Investment, Low Yield: Stagnant per-capita GDP has occurred against a backdrop of high investment-to-GDP ratios, often reaching approximately 30 percent. This implies that capital is being deployed in a highly inefficient manner compared to peer economies where similar investment ratios drive rapid productivity gains.

- The Debt-Propelled Dynamic: Critics argue the economy remains driven by debt servicing and portfolio management rather than exports. The lack of commitment to value-added production means that even as debt is lowered, the economy remains stuck in a “low growth, high cost” trap.

Post-COVID Performance: Recovery vs. Real Expansion

The 4.6 percent to 5.2 percent growth rates recorded in the 2021–2022 period are often touted as proof of expansion; however, a granular analysis suggests these figures represent a “rebounding” effect rather than structural growth.

- Low Production Base: Much of this growth reflected a recovery from the low production base caused by the pandemic and subsequent weather-related shocks like Hurricane Beryl.

- Sterilization of Wealth: The BOJ’s continued build-up of the NIR (tracking at over US$6 billion) ensures that the capital inflows—driven primarily by pre, during, and post-COVID Direct Remittance Inflows (DRI) and not tourism, as approximately 80 percent of tourism revenues are expropriated—are largely sterilized in reserves to maintain JMD liquidity at devalued rates, rather than being used to address the “must-fix” issue of growing value-added exports.

- Marginalized Real Growth: Growth normalized to 2.6 percent in 2023 and fell to 1.3 percent in 2024 as the “rebound” effect waned. Current projections expect growth to settle at a potential rate of only 1.6 percent once post-shocks recoveries are complete.

The Financial Cost of Defensive Hoarding

Maintaining high buffers is not cost-free. Analysis by Jochen Schanz (Senior Economist, BIS) highlights that accumulating reserves is functionally equivalent to issuing debt to invest in foreign assets.

- Negative Carry: Jamaica earns only 3–5 percent on the US Treasury bills in its NIR while paying significantly higher interest rates on its sovereign debt.

- Opportunity Cost: The cost of holding reserves, as proxied by sovereign bond spreads, appears to be a minor consideration for the BOJ compared to the manufactured goal of “sudden stop” prevention, even as it crowds out high-multiplier domestic investment in value-added sectors.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Capital for Structural Transformation

The re-evaluation of Jamaica’s reserve policy indicates that the current “fortress” posture serves an amorphous investment framework where speculators optimize returns through currency volatility and stock market cycles rather than real sector expansion. The “inefficiency factor” remains the primary obstacle: capital is being hoarded in reserves or used to pay for non-value-added imports while the real economy remains stagnant.

The 5 percent growth recorded post-COVID was a temporary return to pre-crisis levels, not a structural breakthrough. To achieve the 5%+ growth rates of African peers like Ethiopia or Rwanda, Jamaica must move beyond defensive hoarding and “manufactured anxiety.” This requires a shift from superficial import substitution and repackaging to genuine value-added production. By deploying “dead capital” from the NIR—wealth generated primarily by the diaspora through remittances—into innovative infrastructure and export-oriented manufacturing, Jamaica could finally translate its hard-won fiscal discipline into sustainable prosperity.

Leave a comment