The 1989 exhibition Into the Heart of Africa at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) stands as a definitive case study in the failure of institutional reflexivity and the collapse of traditional curatorial authority within the context of a rapidly diversifying multicultural society. Originally envisioned as a progressive, postmodern critique of the colonial foundations of ethnographic collections, the exhibition instead became a focal point for racial conflict, legal aggression, and a profound national debate over the ownership of history. The controversy was not merely a misunderstanding of academic irony but a fundamental clash between the “new museology”—which sought to interrogate the museum as a “text” or “fiction”—and a community for whom the colonial past was a source of ongoing trauma rather than a theoretical playground. The subsequent mobilization of the Coalition for the Truth About Africa (CFTA), the legal battles involving a $160,000 lawsuit, and the eventual 2016 formal apology delineate a twenty-seven-year trajectory of institutional reckoning and reform.

The Intellectual Climate and the Genesis of the Exhibition

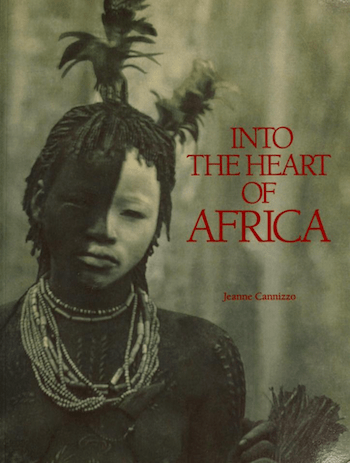

To understand the magnitude of the ROM’s failure, one must analyze the institutional and academic environment of the late 1980s. Under the leadership of Director Cuyler Young, the ROM attempted to embrace a “reflexive” approach to its collections, moving away from the pretense of objective scientific display toward a self-critical examination of how objects were acquired. The curator, Jeanne Cannizzo, an anthropologist with expertise in West African art, designed the exhibit to be a “critical, self-reflexive examination” of the museum’s own African collection, which had been primarily amassed by Canadian soldiers and missionaries during the peak of European imperialism between 1875 and 1925.

The curatorial intent was rooted in the “new museology,” a movement that argued museum practices themselves should be the subject of scrutiny. The objective was to expose the biases and paternalistic attitudes of the Victorian and Edwardian eras by presenting the artifacts through the eyes of the original collectors. In this framework, the artifacts were not meant to represent “Africa” in a broad sense; rather, they were intended to document the “misappropriated byproducts” of military and religious fervor. The exhibit invited viewers to analyze the museum as a “charnel house” of dead civilizations and to recognize the “fiction” created by the curator and the visitor alike.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Institutional Objectives and Community Realities

Aspect of Exhibition

Curatorial/Academic Objective

Lived Community Experience

Primary Subject

The biography of the Canadian collectors

The erasure of African artistic and cultural agency

Narrative Tool

Postmodern irony and theoretical distancing

Visceral re-traumatization through racist imagery

Object Status

Seen as “specimens” of a colonial history

Seen as stolen cultural and spiritual heritage

Institutional Voice

A self-aware, critical narrator

An authoritative, exclusionary “white” voice

Pedagogical Goal

To teach the history of imperialism

To reinforce stereotypes in the minds of the public

The Architecture of Irony: An Artifact-by-Artifact Analysis of Failure

The primary mechanism through which the exhibition alienated its audience was its reliance on irony—a sophisticated literary and visual device that requires a shared set of assumptions between the producer and the consumer. In a museum setting, which is historically viewed as an arbiter of truth, the use of irony is fraught with danger. The “Into the Heart of Africa” exhibit failed because it presented racist historical viewpoints with the expectation that the audience would automatically perceive the museum’s disapproval.

The Entrance and the Hallway of Conflict

The physical layout of the exhibit was designed to immerse the visitor in the “darkness” of the colonial era. Visitors entered through a hallway that featured a life-sized photograph of a British soldier plunging a sword into the chest of a Zulu warrior. For Cannizzo, this was a stark reminder of the violence inherent in the colonial project. However, for many African-Canadian visitors, this was a gratuitous and painful display of white-on-black violence that set a tone of hostility from the outset.

As visitors moved deeper into the exhibit, they encountered displays dedicated to “imperial commanders” and “missionary explorers”. One of the most contentious displays featured a 1910 photograph depicting a white female missionary giving a “lesson in how to wash clothes” to African women. The curatorial intent was to highlight the absurdity and arrogance of the “civilizing mission”. Yet, for the community, this was an offensive reinforcement of the stereotype that Africans were helpless and ignorant until Westerners arrived to teach them basic hygiene.

The Missionary Video and the Failure of Context

The exhibit also utilized multimedia to present its “critique.” A video dramatization featured a missionary mocking African customs and applauding those who converted to Western clothing and religion. While the video ended with a disclaimer stating it was a fictional account intended to show a missionary’s perspective, many visitors left the display before the ending. To these viewers, the museum was simply broadcasting racist sentiments without sufficient framing. This demonstrated a profound failure in understanding how public audiences consume museum content; unlike an academic text, a museum exhibit is often experienced non-linearly and partially.

Table 2: The Semioptics of the Exhibit’s Visual Language

Visual Element

Intended “Critical” Reading

Actual “Received” Message

Zulu Warrior Photo

Documentation of imperial brutality

Glorification of violence against Black bodies

Washing Lesson Photo

Satire of the “civilizing mission”

Reinforcement of African “helplessness”

Collector Journals

Evidence of Victorian prejudice

Elevation of the white colonial narrative

Missionary Video

Ironic portrayal of religious arrogance

Institutional validation of racist mockery

Display Labels

Reflexive interrogation of museum practice

Authoritative statements of cultural fact

The Mobilization of the Coalition for the Truth About Africa (CFTA)

The backlash against the exhibit was not immediate but grew steadily as members of the Black community began to experience the show. In January 1990, a group of prominent leaders, including lawyer and activist Charles Roach, were invited to a private viewing. Roach observed that the reaction was one of visceral pain, with some participants becoming “so chilled” by the opening sections that they refused to see the rest. Roach articulated the core grievance: the museum was telling the “truth” from the perspective of the enslavers and colonizers, while failing to tell the “whole truth” of African agency and resilience.

In response to the ROM’s refusal to modify the show, the Coalition for the Truth About Africa (CFTA) was formed. The group was a broad-based alliance including Christians, Muslims, Rastafari, and Orisha practitioners, representing a cross-section of the African diaspora in Canada. Led by individuals such as Rostant Ras Rico John, Afua Cooper, and Silbert Barrett, the CFTA demanded the immediate closure of the exhibit and a commitment to collaborative curation.

The Strategy of Resistance

The CFTA’s strategy involved a sophisticated blend of intellectual critique and direct action. Every Saturday for several months, the group picketed the museum, chanting slogans and distributing pamphlets that challenged the exhibit’s premises. They famously rebranded the institution as the “Racist Ontario Museum,” a moniker that successfully shifted the public narrative from a debate over art to a debate over systemic institutional racism. The protests became a focal point for broader grievances in Toronto, including the police shootings of Black youth and the perceived exclusion of Black history from Canadian education.

The Picasso Analogy: A Masterstroke of Institutional Critique

One of the most enduring legacies of the CFTA’s intellectual resistance is the “Picasso analogy” formulated by Silbert Barrett. Barrett pointed out the hypocrisy in how the ROM treated African art versus how Western institutions treated European art. He argued that if a museum were to hold an exhibit on Pablo Picasso, the focus would be on Picasso’s individual genius, his technique, and his creative intent. The person who purchased the painting would be a footnote. However, in Into the Heart of Africa, the African creators remained anonymous—referred to as “unknown”—while the names of the white soldiers and missionaries who “collected” the items were paraded as the central figures of the narrative.

This analogy highlighted the “denial of coevalness”—the tendency of Western museums to place African cultures in a stagnant, mythical past while viewing European history as a dynamic, unfolding narrative. By centering the exhibit on the 1875-1925 period, the ROM was not just documenting colonialism; it was, in the eyes of the CFTA, “freezing” Africa in a state of subjugation and denying its living, contemporary significance.

Table 3: Theoretical Disparity in Artistic Presentation

Feature

Treatment of Western Artist (e.g., Picasso)

Treatment of African Artist (at ROM)

Naming

Celebrated as an individual creator

Erased or categorized as “tribal”

Agency

The artist is the primary subject

The object is a byproduct of the collector’s life

Context

Artistic evolution and innovation

Military conquest and religious mission

Temporal Status

Dynamic and influential on the present

Static and confined to the colonial past

Ownership

Intellectual property of the creator/estate

“Souvenirs” and “specimens”

Escalation and the $160,000 Lawsuit: The Institutional Response

As the protests grew in intensity, the ROM’s leadership adopted a defensive and litigious stance. Director Cuyler Young argued that the museum was a “democratic” institution and that closing the exhibit would set a dangerous precedent, potentially allowing any group to “close a show” they found offensive. This stance ignored the asymmetrical power dynamics between a billion-dollar public institution and a marginalized community group.

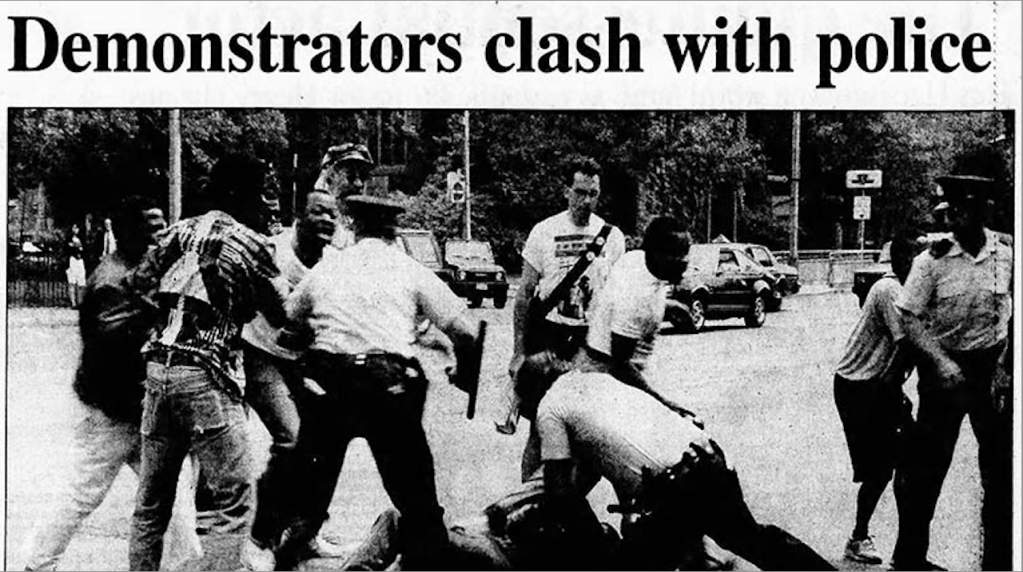

The Violence of June 2, 1990

The tension reached its breaking point on June 2, 1990, during a confrontation between the police and the demonstrators outside the museum. The conflict resulted in injuries to three police officers and the arrest of eight protesters, including the CFTA leader Adisa Oji. The museum then took the unprecedented step of obtaining a legal injunction that barred protesters from coming within 50 feet of any entrance.

Financial Intimidation as a Curatorial Tool

Perhaps the most damaging institutional decision was the ROM’s choice to sue the CFTA for $160,000 in damages. The museum claimed this amount represented lost revenue from ticket sales and the additional costs of security required by the protests. While Young later claimed that the museum never actually intended to collect the money, the lawsuit was perceived by the community as a heavy-handed attempt to bankrupt and silence its critics. This legal aggression solidified the ROM’s reputation as a “fortress” and further alienated the very community it hoped to engage through its “reflexive” exhibit. The suit was eventually dropped in 1993, but the damage to the ROM’s credibility was already permanent.

The Failure of Academic Reflexivity and the Scholarly Rift

The ROM controversy also exposed a deep rift within Canadian academia. Many anthropologists and museum studies scholars initially defended Jeanne Cannizzo and the exhibit. They argued that the CFTA’s reaction was “unsophisticated” and that the protesters failed to grasp the postmodern nuance of the curatorial intent. This defense, however, was criticized by the CFTA as a form of intellectual racism that prioritized academic theory over the lived experiences of marginalized people.

For the protesters, the “truth” was not a postmodern construction to be played with in an ironic display; it was a matter of historical justice and the dignity of their ancestors. Afua Cooper noted that the “irony” was completely lost on the many white school-age children who attended the museum, for whom the exhibit simply reinforced racist stereotypes of Africa as a “dark and lost continent”. This highlighted a fundamental paradox: a museum exhibit that requires a PhD to be understood as “anti-racist” is, in its public function, essentially racist.

Table 4: The Rift in Interpretive Authority

Perspective

Basis of Authority

View of the Exhibit

Institutional/Academic

Postmodern theory and anthropological expertise

A sophisticated critique of colonial history

Community (CFTA)

Lived experience and ancestral heritage

A racist perpetuation of colonial trauma

Legal/Police

State mandate and public order

General Public

Traditional trust in the museum as “Truth”

Confusing, often reinforcing existing stereotypes

The Global Aftermath: The Exhibit as a “Cautionary Tale”

The fallout from Into the Heart of Africa had immediate and far-reaching consequences for the museum world. As the controversy reached an international audience, the ROM’s reputation suffered significantly. Four major North American museums, including the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and museums in Los Angeles and Houston, cancelled their scheduled bookings for the exhibit’s tour. These cancellations were a clear signal that the ROM’s approach was no longer viable in a post-colonial world.

Reforming Museology and Community Consultation

The exhibit is now a foundational example in museum studies programs of “what not to do”. It served as a catalyst for a permanent shift in how museums interact with “source communities”—the cultural groups whose artifacts are being displayed. Today, it is considered standard practice for institutions to engage in “collaborative curation,” involving community members in every stage of an exhibit’s development, from the initial concept to the final labels.

The controversy also accelerated the conversation around “repatriation”—the return of artifacts to their countries of origin. As the public became more aware of how these items were acquired as “misappropriated byproducts” of military fervor, pressure mounted on museums to return looted items, such as the West African bronzes and the Nkisi nkondi power figures.

Table 5: The Evolution of the Museum Model (1989 vs. Present)

Feature

Pre-1989 “Authoritative” Model

Post-Controversy “Collaborative” Model

Decision Making

Internal, curator-led

Shared with community advisory boards

Expertise

Academic/Scientific

Academic + Traditional/Community Knowledge

Tone

Authoritative or Ironic

Transparent, Ethical, and Dialogical

Goal

Preservation and Education

Social Responsibility and Restorative Justice

Conflict Resolution

Defensive/Litigious

Reconciliation and Apology

The Long Road to Reconciliation: 1990-2016

For nearly twenty-five years, the ROM remained largely silent regarding the trauma caused by the exhibit. It was not until the fall of 2014 that a significant shift occurred with the launch of the “Of Africa” symposium, which was intended to rekindle the conversation and address the “colonial wounds” that had never truly healed. This initiative was motivated in part by the renewed efforts of the CFTA, which had continued to push for a formal apology.

The 2016 Formal Apology

On November 9, 2016, twenty-seven years after the exhibit opened, the ROM issued an official apology to the African-Canadian community. Dr. Mark Engstrom, the museum’s Deputy Director of Collections and Research, read a statement expressing “deep regret” for the museum’s role in contributing to anti-African racism. The apology acknowledged that the exhibit had “inadvertently perpetuated an atmosphere of racism” and reproduced the “colonial, racist, and Eurocentric premises” through which the collections were acquired.

The apology was graciously accepted by Rostant Ras Rico John, who remarked that “when a wrong has been done, it has to be righted”. The event was a watershed moment for the Toronto Black community, with Afua Cooper noting that it “removed a burden” and allowed the community to finally “exhale”.

Restorative Initiatives and Future Outlook

Beyond the verbal apology, the ROM committed to several tangible steps to repair its relationship with the African-Canadian community:

- Museum Internships: The creation of two annual internships for young Black people to gain experience in museum research and curation.

- Educational Partnerships: Increased collaboration with Black educational networks to ensure programming is inclusive and historically accurate.

- “Of Africa” Project: A multi-year commitment to hosting exhibits and lectures that highlight the diversity and contemporary vitality of the African continent.

- Contemporary Art Focus: A shift toward featuring named, active Black creators, such as the major 2018 exhibition dedicated to Black contemporary artists.

Conclusion: The Finality of the Picasso Analogy

The statement by Silbert Barrett regarding the “Picasso analogy” remains the most succinct and powerful critique of the Into the Heart of Africa controversy. It exposed the fundamental hypocrisy of a Western institution that claimed to value “art” while treating the creations of non-Western peoples as mere ethnographic specimens or colonial souvenirs. By centering the collector over the creator, the ROM failed in its mission as a public educator and instead became a site of cultural trauma.

The resolution of this controversy demonstrates that the “truth” about Africa cannot be found in the ironic reflections of colonial history, but must be told by the people whose lives and heritage are at stake. The shift from the “Racist Ontario Museum” of 1990 to the apologetic and reforming institution of 2016 marks a significant, albeit delayed, victory for the Coalition for the Truth About Africa. The “cautionary tale” of the ROM ensures that future generations of curators will approach the “heart of Africa” not with ironic distance, but with the humility, consultation, and respect that all cultures deserve.

Works cited

1. Challenging Racism in the Arts: Case Studies of Controversy and Conflict 9781442672802, https://dokumen.pub/challenging-racism-in-the-arts-case-studies-of-controversy-and-conflict-9781442672802.html 2. Religion and Public Life in Canada: Historical and Comparative Perspectives 9781442679191 – DOKUMEN.PUB, https://dokumen.pub/religion-and-public-life-in-canada-historical-and-comparative-perspectives-9781442679191.html 3. Contested Representations: Revisiting Into the Heart of Africa 9781442603264, https://dokumen.pub/contested-representations-revisiting-into-the-heart-of-africa-9781442603264.html 4. ARCHIVE: How this 1989 ROM exhibit on Africa became a …, https://www.tvo.org/article/archive-how-this-1989-rom-exhibit-on-africa-became-a-cautionary-tale-for-museums 5. Royal Ontario Museum and the Coalition for the Truth about Africa Release Reconciliation Statement and Engagement strategy, https://www.rom.on.ca/news-releases/royal-ontario-museum-and-coalition-truth-about-africa-release-reconciliation 6. mining the museum: – artists look at museums – Columbia University, http://www.columbia.edu/itc/anthropology/schildkrout/6353/client_edit/week12/corrin.pdf 7. Royal Ontario Museum apologizes for 1989 ‘Into the Heart of Africa’ exhibit | Globalnews.ca, https://globalnews.ca/news/3058929/royal-ontario-museum-apologizes-for-1989-into-the-heart-of-africa-exhibit/ 8. After 27 Years, Royal Ontario Museum Finally Apologizes for Racist Exhibition – Artnet News, https://news.artnet.com/art-world-archives/royal-ontario-museum-racist-exhibition-742205 9. Royal Ontario Museum apologizes over racist exhibit … 27 years later | CBC News, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/rom-apology-into-heart-africa-royal-ontario-museum-1.3840645 10. An apology — and advocacy — that echoes – Dal News – Dalhousie University, https://www.dal.ca/news/2016/11/18/an-apology-that-echoes–jrj-chair-afua-cooper-part-of-coalition-.html

Leave a comment